Los estilos de los ciclistas de La Estrellita

PerúCyclists tend to find La Estrellita difficult to leave. Not that anything about the shabby Cusco hostel itself keeps people there — it’s dingy and cold, with uncomfortable bedding, intermittent water shortages, and owners who are perfectly friendly but not exactly memorable. But, for whatever reason, bike tourists have claimed this unlikely hovel as their home turf in the former Inca capital. The community of other cyclists — a rarity the lives of solo adventurers — turns the grey courtyard into a lively cicloviajero clubhouse.

I, too, lingered at La Estrellita longer than intended. When I finally got on the road again after five days, I felt anxious to make up the time I had lost sitting around eating pancakes among other American tourists. But as I headed out of town, I got a text from Nathan, a La Estrellita resident of multiple weeks: “You have to ride Ausangate,” he told me.

Ausangate, a glacial peak south of Cusco revered by the Incas, is popular today for trekking and mountaineering. Bikepackers who don’t mind pushing their rigs uphill also frequent the trail to savor close-up views of glaciers followed by fun downhill riding.

Alas, I was already on the highway, blasting southward.

“Too late in the season,” I texted back. “Don’t want to get stuck in the thunderstorms.”

While the statement was valid, it was still an excuse. The real reason I couldn’t bike Ausangate was that I had fallen behind schedule, and I needed to make up some time by pounding the pavement.

“Bummer,” Nathan replied. “Tres Cordilleras is rad too,” referring to another bikepacking route that I didn’t have time for.

I shrugged off the suggestion, realizing that even though Nathan and I had similar bikes, similar gear, and similar adventurous spirits, our riding styles weren’t totally aligned. Nathan takes his time to ride only trails, even if their routes are circuitous and even if he has to push his bike uphill. Meanwhile, I split my time between trails and roads, generally only riding off-road when the routes coincide with my southbound trajectory.

Before I embarked on my trip, I didn’t realize what a vast range of styles exist within the niche sport of bike touring. I knew that some cyclists ride on pavement, while others prefer dirt roads and trails, but even in the quirky community of La Estrellita, styles diverge far beyond that basic distinction.

I had first heard of La Estrellita when I crossed paths with Will on a dirt trail in Ecuador. A tall and lanky German with a massive bike made of bamboo, he looked capable of crossing countries in just a few pedal strokes. As is typical when running into fellow bike tourists, I asked where he’d been. He said he had just arrived in Ecuador, via bus from Perú. This surprised me — I had assumed that busses were reserved for people who weren’t strong enough to bike from place to place. Maybe he was pressed for time? My hypothesis was quickly debunked when he told me he had spent four months at La Estrellita in Cusco, using the city as a home base to do shorter, lighter weight rides in the area, such as Ausangate.

“I used to tour,” he explained, “but now I just like to travel around doing shorter rides.”

“That makes a lot of sense,” I said, pondering the benefits of being able to spend more time riding fun trails and getting to know specific regions better. “But that’s not what I’m doing. I want to ride across the continent.”

“That’s good, too,” he said, “just different.”

Martin, a Czech cyclist I met at La Estrellita, had a similar athletic build to Will, but sat at the opposite side of the cycling style spectrum. “I probably ride faster than you,” he told me in our first interchange. He had originally planned to cross the continent in less than three months, compared to my ten. His bike sported a carbon frame, aerodynamic time trial handlebars and skinny gravel tires. He didn’t carry a stove, lugging only minimal camping gear and one change of clothes. He told me he often cycled late into the night to cover more ground. This guy means business, I thought.

But La Estrellita had derailed his timeline. He’d been staying there two weeks already when I arrived. Every morning, I’d see him working on his bike, saying he would leave today. Every afternoon, I’d see him still in his spandex, smoking a joint and saying that the weather wasn’t quite good enough and that he might leave tomorrow.

Differences at La Estrellita didn’t only arise in riding styles, but also in travel styles. Iohan and Mathilde, a pair of smiling French cyclists, eschewed all forms of conventional tourism, camping nearly every night of their journey and complaining about guided tourists who got in their way on the local Inca trails. On the other hand, Emily, who was taking a break from cycling by working at a California-style vegan restaurant in Cusco, seemed hardly to have ventured outside the tourist bubble. I was shocked when she asked me what a “caldo de gallina” was — frequently the only dish available at roadside restaurants in Perú.

Before I started the trip, I thought I might meet fellow cyclists and ride with them. But by the time I left Cusco, I’d gone 4000 miles and 5 months without any riding partners. After meeting the diverse crowd at La Estrellita, I thought I might never meet anybody who rides in the same way I do.

But one thing all these cyclists had in common was a resounding positivity for their journeys and a genuine interest in learning about others’ journeys. That enthusiasm proved to be the glue that kept everyone stalling at La Estrellita, a place where our different speeds, routes, and budgets didn’t stand in the way of community.

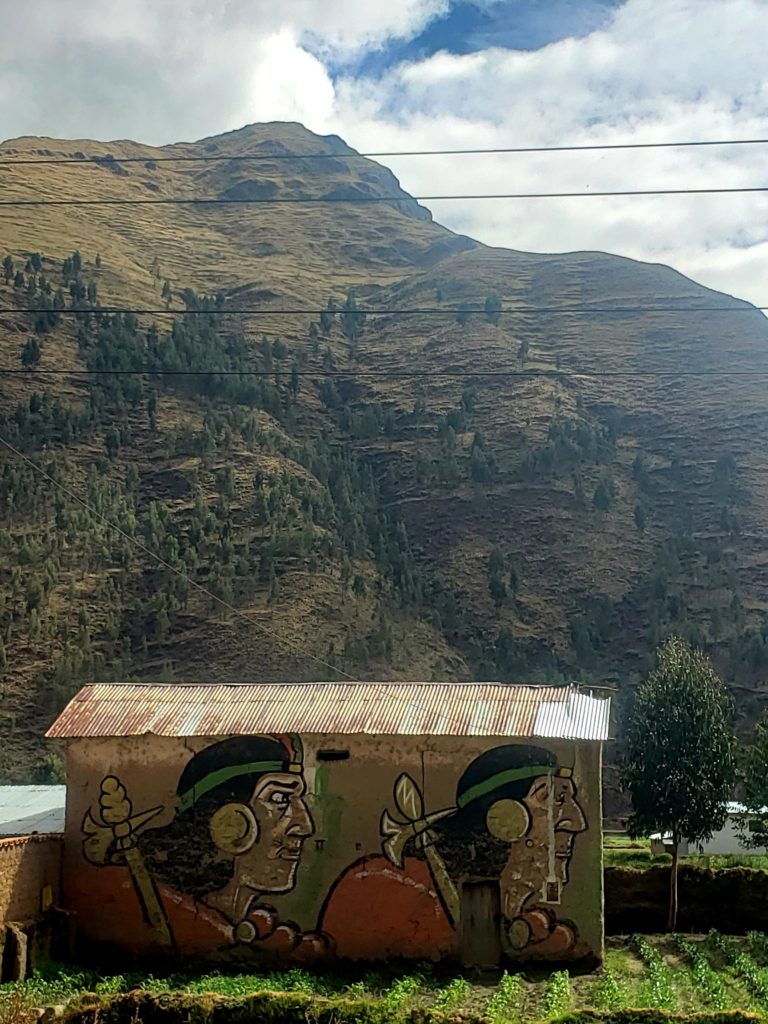

Two days of highway took me from Cusco over one last high mountain pass, onto the edge of the altiplano, a vast plateau at 12,000 feet above sea level. Rather than resenting the road, or wishing I was riding Ausangate, I relished riding quickly across the barren landscape with the breeze blowing in my face. I stopped at roadside stands to eat unique foods like cuy (roasted guinea pig) and giant chicharrones (fried pork rinds). I saw Inca ruins along the highway, and chatted with locals in little towns.

I thought about a conversation I’d had with Nathan, when I asked him how he’d liked a certain city in Bolivia. He told me it was alright, but that, “I didn’t come to South America for the cities, I came for the outdoors,” stressing “outdoors” in a reverent manner with his Australian accent.

By contrast, I came for the cultural experiences just as much as the wilderness experiences. And since most of the population lives closer to the highways than the trails, the pavement provides an integral part of my journey.

Dark clouds chased me into the town of Pucará. As I checked into a funny little hospedaje in the backyard of a diner, hail started pelting in the street. I breathed a big sigh of relief that I wasn’t stuck camping on the flank of Ausangate. Then I saw a few other bicycles leaning against a wall. One of them I recognized — it belonged to Holly! I’d met Holly a month earlier in Huaraz. She was headed south on a similar timeline to me. We’d camped together once, and we’d hung out again at La Estrellita, but we’d never logistically worked it out to ride together. I had more in common with Holly than most. Also from California, she got into bike touring from a cycling background, as opposed to many of the others, who had been hitchhikers, backpackers or other sorts of travel vagabonds before buying a bike. Holly also seemed to share a similar travel philosophy to me, by mixing the efficiency of roads with periodic adventures on the trails.

Surprised to run into me yet again, Holly introduced me to a British couple she’d met on the road, Noel and Carolyn. The two of them were on their way from Lima to Santiago on skinny-tired road bikes. The four of us huddled around hot teas as hail clattered on the tin roof. We decided we would all ride together the next day to the city of Puno on the shore of Lake Titicaca.

We woke up to find a thin layer of snow covering the streets of Pucará, a light drizzle in the air. Had I been alone, I might have gone back to bed. But with the accountability of my three new friends, I found myself with all of my warm clothes on at 8am, cycling into bleak white and brown hills. What would have otherwise been a cold day with unspectacular scenery turned into a lively adventure getting to know my new companions. Arriving in Puno, the four of us toasted pisco sours over dinner at a fancy restaurant. Dinner with friends! What a novelty.

The next day, we all went our separate ways. After all, our cycling styles still differed. I wanted to take a day off to see the floating reed islands of Lake Titicaca, while Holly preferred to avoid the tourist crowds and continue biking. Noel and Carolyn would continue on the highway, whereas I wanted to ride a mountain bike route on the edge of Lake Titicaca. We said our goodbyes and hoped to meet up at some point later on.

But for one day, having companions on the bicycle sure felt great!

1 comment

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Great post as always. Love the reflections on the bike touring community and its diversity. Touring can be a lonely endeavor, but, paradoxically, one of its most redeeming qualities is the entry into the community of tourers.

I’ve only ever bussed through Juliaca, ~3 years ago, but it has stuck with me ever since as maybe the ugliest place I’ve ever been. Funny that you had the same impression.