El golpe de mi recorrido

BoliviaThe timing couldn’t be better! On October 20, the Plurinational State of Bolivia held presidential elections as I was inching toward its northern border on my bicycle. I’ve tried to be a student of politics, history and current events in each country I pass through. I figured that the election season in Bolivia would surely provide a catalyst for incredible insights into the country’s culture. I planned to spend a month in the country, biking through the big cities of La Paz and Sucre, but also the poorer rural areas in the high plateau of the altiplano and the mountainous rainforest known as the yungas. I hoped that this regional diversity would provide thrilling context for the political landscape.

The incumbent, Evo Morales, had already fascinated me long before the election. He had held office for fourteen years and was running for his fourth term. Morales’ government is one of the only examples of socialism not destroying a Latin American economy (although to be fair, the CIA destroyed many Latin American socialist regimes before socialism had a chance to destroy their economies). Rather, Bolivia has experienced steady growth and stability under his tenure — a remarkable achievement for one of the poorest countries in the Americas. Morales commands immense popular support as the first indigenous leader of a South American country. After a long history of persecution of the indigenous majority, Morales came to power on a campaign to rid the country of predatory foreign influence and return its natural wealth to indigenous laborers. His aims were respectable, even if his methods were not altogether economically sound.

But the longer Morales held power, the more he began to look like a classic Latin American strongman dictator. The constitution, which he had helped write, imposes presidential term limits, but he ignored them when he ran for his third term, by virtue of winning a popular referendum excusing him from the term limits. International organizations such as the United Nations (UN) and the Organization of American States (OAS) grumbled over the constitutional loophole, but couldn’t deny the democratic justification when Morales won over 60% of the vote for the third time.

Approaching his fourth election in 2019, Morales held the same referendum — but he lost. The country voted to not allow Morales on the ballot. So instead, he obtained a corrupted court decision allowing him to run anyway, drawing more direct international condemnation and foreshadowing a tumultuous election.

~

I followed the news on election day from the road in southern Perú, refreshing a google search whenever I got service. Live reporting of results showed Morales holding a lead over his closest opponent by about eight percentage points, with 44% of the vote. If Morales didn’t win by either ten percentage points, or with at least 50% of the vote, the election would go into a runoff between the top two candidates in November. Perfect, I thought. That way, I would get to witness the runoff campaign while biking through the country.

But then the election officials curiously stopped reporting results. Twenty-four hours later, they announced Morales leading by just more than the ten percentage points he needed to avoid a runoff. Morales officially declared his victory.

International observers, in particular the OAS, which monitors regional elections, expressed skepticism at the trend of events. In a runoff, Morales stood a good chance of losing, since factitious opposition parties would likely unite against him. The opposition leaders cried, “fraud,” and encouraged their followers to take to the streets. Protests erupted in major cities, particularly La Paz and Santa Cruz, where the right-wing, anti-Morales parties hold sway due to the concentration of wealth.

But I was still a few weeks away from the Bolivian border while all this was happening. Surely, things would calm down by the time I arrived, I thought.

~

In the weeks following the election, the protests only worsened. Protesters set fire to government buildings and multiple deaths were reported. In some areas, local police forces had joined the protests. By the time I arrived in Cusco, Perú, on November 4, political pressure had forced Morales to permit the OAS to conduct an audit of the results.

On November 10, the OAS reported “clear manipulation” of the IT systems underlying the election process, declaring that they could not validate a Morales victory. Embarrassed, Morales offered to hold new elections.

I read the news as I settled into my hotel in Puno, Perú’s southernmost major city, only two days of biking from the Bolivian border and four days from the capital city of La Paz, which had become the center of the protests. What great timing, I thought. Finally, the protesters were validated — democracy would be restored with new elections and I could bike on through while observing an transparent, peaceful discourse over what would happen next.

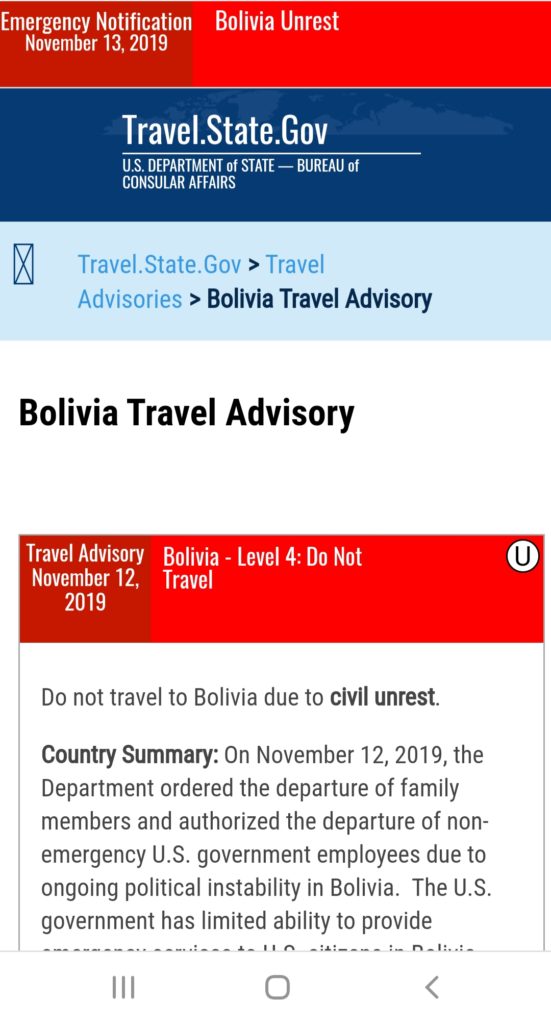

But to my dismay, the protests only intensified in La Paz following the OAS report. An email from the US State Department informed me that they had elevated the travel advisory for Bolivia to red, “Do Not Travel.” I contacted the hostel where I had planned to stay in La Paz, whose owner had previously told me that the situation was stable enough for tourism. They now told me not to come, but to follow up as things were changing daily. Martin, a cyclist I’d met at La Estrellita in Cusco, was more blunt when I texted him. He had raced ahead of me and was now stuck in La Paz. “Don’t come here,” he told me. “These people are crazy.” I sent emails to a few more loose contacts in Bolivia, all of whom expressed skepticism toward entering the country. But all these reports were based on La Paz, which most travellers can’t avoid. What if I went around La Paz?

I walked over to the Bolivian consulate in Puno. They echoed the recommendation to avoid La Paz, but said that the countryside should be fine. So I mapped an alternate route around La Paz, which proved tricky since nearly all roads in the north of the country go through the capital city. I contacted a hotel in Copacabana, Bolivia, a tourist destination on the shore of Lake Titicaca only a few miles from the border with Perú. They told me that all had been quiet in Copacabana itself, although transfer services to La Paz were not possible. I decided I’d make it to Copacabana and reevaluate the options — perhaps the riots would calm in the next few days.

I geared up to leave Puno, toward Bolivia, when I read that the commander-in-chief of the Bolivian army suggested that Morales should resign to “pacify and maintain stability” in the country. In a reversal of his previously defiant messages, Morales promptly followed the army chief’s suggestion and fled Bolivia for Mexico (where the leftist government of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador welcomed his exile). Great, I thought. Morales is gone; the protestors got what they want. Now everything should calm down, just in time for me to enter the country. Right?

~

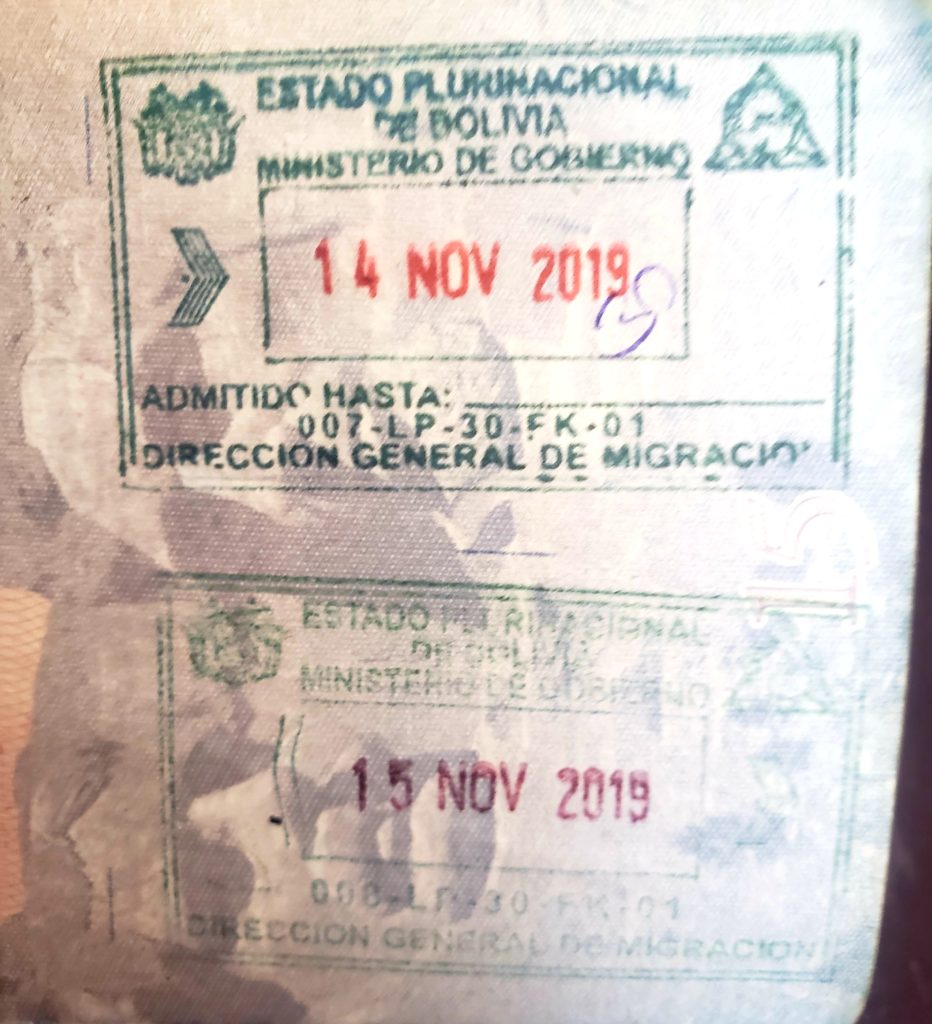

“¿Sabe de los problemas en Bolivia?” the border agent asked me skeptically as he stamped my passport. I explained to him my plan and he said I’d probably be fine if I avoided La Paz.

A surprising number of people were hustling through the border — but all in the opposite direction. Disappointed tourists were leaving Copacabana, into Perú. They told me that roadblocks had prevented any transportation from reaching La Paz, so their organized tours had been turned around. They weren’t sure what they would do next, although they didn’t need to think much since their tour guides were in charge.

“A bicycle! That’s the way to do it!” one of them exclaimed as I pedaled into Bolivia.

~

Copacabana’s streets reflected none of the hustle of the border; only quiet, in both a relieving and eerie manner. No signs of protests, but not many signs of life, either. I checked into my hotel and caught up on the latest news.

Now in Mexico, Morales was screaming “golpe d’estado,” — coup d’etat — to the media. He accused the United States and the OAS of a racist conspiracy to remove him from power. He encouraged his supporters to resist the interim government and promised that he would return to restore indigenous power. So while the protestors from previous weeks celebrated, new riots erupted in the poorer areas of La Paz. In rural areas, Morales supporters set up roadblocks, blocking transportation along both major highways and dirt tracks, effectively putting major cities and their economies under quarantine.

Meanwhile, the interim government didn’t help to calm the situation. Jeanine Áñez declared herself interim president by virtue of being the right-wing congressional leader. She promised that her only role was to pacify the country until new elections could be held expediently. But her actions betrayed that purpose. She appointed a new cabinet without any indigenous representation. She declared that Morales’ socialist party would not be eligible to participate in the new elections and that Morales would be wanted for arrest should he return to Bolivia. She moved to normalize relations with the United States, which had been diplomatically estranged by Bolivia for many years under Morales. She turned the army and police against indigneous protesters, after they had been neutral during the right-wing protests.

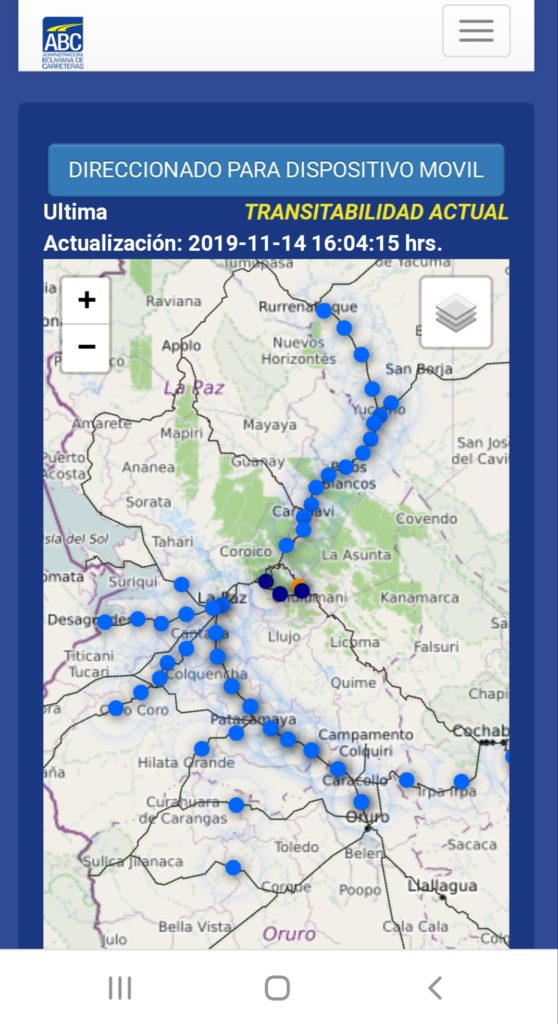

“The situation is very bad,” Maurice told me, the French owner of the hotel in Copacabana. “I would suggest that you wait a few days before you start traveling.” He showed me an online map that pinpointed the known location of roadblocks across the country. Several were positioned along the rural route I had planned on riding.

Roadblocks are common in Bolivia, he explained — the rural population frequently protests in this manner when they aren’t getting what they want from the government, which is often. “Normally, we give them a bag of coca leaves and a few beers and they let us through in taxis,” he said. Bikes can usually bypass the blockages without the bribes.

“But this time is different,” he continued. “They are very, very angry. And they are angry at the white man. And you might be fine, because most of them know that you are not the same white man who took away their voice. But it only takes one of them, that is not so smart, to cause a problem. And I would avoid telling anyone that you are from the United States, because many believe the United States is behind the coup.”

I weighed the conflicting advice of Maurice and the Bolivians that I’d spoken with at the consulate and immigration. I figured that Maurice would naturally be risk-averse in his advice. And it sure would be an adventure to bike past roadblocks in the Bolivian countryside! But I was exhausted — and nervous. I hadn’t slept well while camping the prior night, and I needed a good night’s rest in a bed. I decided that I would sleep in and stay the next day in Copacabana, while trying to solicit more opinions from Bolivians in town. And, who knows, maybe the situation would calm overnight.

~

Noel and Carolyn, the friends I rode with the previous week, had also made it to Copacabana. They joined me for dinner at my hotel. They didn’t have a plan. They couldn’t take the route I had mapped because the dirt roads would be too rough on their road bikes. The only paved roads go through La Paz. They thought they’d spend a day or two in Copacabana to wait and see if the situation would improve.

As we were ordering dessert, I said something to our waiter to Spanish, which surprised him since most of the hotel’s guests were Europeans and Americans.

“Hablas español muy bien,” he told me.

“Gracias,” I said, flattered.

“Quiero decirte. Mañana, habrá una manifestación de la una en la plaza.”

“¿Manefestación?” I asked, confused. There would be a manifestation? What did that mean?

“Si, todo el pueblo estará cerrado. Acá, al hotel, todo bien, no te preocupes.”

“Entonces — ¿si tenemos que comprar cosas, hacemos por la mañana?” I asked.

“Si,” he said.

Noel and Carolyn, who don’t speak Spanish, were lost. “What’s going on?” they asked me.

“He said there will be a ‘manifestation’ tomorrow,” I explained. “I’m not sure exactly what that means, but everything in town is closing after one. So if we need to take care of anything, we should do it in the morning.”

“Maybe it is like a town meeting?” Carolyn offered. Nobody said “protest” but we were all thinking of it. We had all been assured that Copacabana, a town reliant on tourism, wouldn’t have protests.

But I looked up the translation of “manifestación” later that night, and sure enough, it doesn’t mean “manifestation,” it means “protest.”

~

A loud bang jolted me awake. Where am I? I rolled over. The bang again. Knocking on the door. “Excuse me?” A French accent.

“Uno momento.” I got up slowly and looked at my phone. 10:45pm, but I had been asleep for a couple hours already. I slipped on some long underwear and opened the door.

“I am so sorry for waking you,” Maurice, the hostel owner, said. I was pretty grumpy that he had woken me, too. I really needed my sleep, tonight of all nights. I said nothing, waiting for his explanation.

“I was just informed that the border with Perú will be closing tomorrow at 8am,” he said in a stressed voice. “I want to make sure you know so you have the option to leave and you don’t get stuck here since you can’t go to La Paz, for I don’t know how long.”

“Okay…” I muttered, trying to process the information.

“We will start breakfast tomorrow at 7 and we can talk about it. Again, I am so sorry for waking you.”

“No, thank you,” I said as I shut the door and heard him rapping on the door of the next room.

I hadn’t been planning on going back to Perú, but it had been a last resort option in the back of my mind, reserved only if things got worse. Now, I didn’t have any time to ask around town about the situation — and if I stayed, I’d be dealing with a protest. I had to decide whether to leave tonight. Or in the morning, at breakfast, when Maurice would explain the situation more clearly. But I needed to be prepared to leave. Biking back to the border would take a half-hour, at least. I had to pack, too. And – shit – I hadn’t gone to the ATM to get bolivianos yet, and I had to pay Maurice. I set my alarm for 6:30am and tried to get the rest I sorely needed.

But I still couldn’t sleep. My mind raced. Earlier, I had felt confident about going into the country despite the protests and roadblocks. After all, journalists do that sort of thing all the time. I would learn so much! But now it made me feel sick. What would I do if I ran into trouble? If I were robbed of my bike in the anarchy? What gave me any reason to feel confident, that everything would be fine? That I knew better than Maurice, than the US State Department, than everyone suggesting I should not go into Bolivia? What had I been thinking?

And what would I even do if I went back to Perú? The only other way I could continue south was into Chile, and the only border between Perú and Chile is on the coast, nearly 250 miles away through mountainous terrain with very few settlements. I didn’t know whether I would be able to find food or lodging along the way, and I certainly wasn’t in the frame of mind to plan a backcountry expedition. And then I would arrive in Chile — a country which was also experiencing historic, destructive protests. Only days before, demonstrators had burned down a grocery store in Arica, the town I would cross into on the coast. It didn’t seem much better.

As my mind swirled with stress, a sacreligious thought surfaced. Should I go home? I have always said that if I’m not having fun, I wouldn’t be ashamed to pull the plug on this trip. That moment certainly wasn’t fun, unable to sleep while stressing about riots. I tried to think back to the weeks prior, when I was in heaven biking through the jungle, climbing around Machu Picchu, making friends on the roads — this has got to be temporary, I thought. I just need to get someplace I can rest.

At some point I fell asleep, contemplating the options over and over and over again, until the choices felt repetitive and unproductive, like sheep jumping over a fence, those sheep grazing brown grass in the few miles of Bolivia I’d passed through, sheep that grazed blissfully unaware of the political tumult around them. So I slept.

~

I woke before my alarm, naturally.

I went out to the town square to get cash from an ATM. I still hadn’t decided what I would do, and wanted to hear what Maurice had to say at breakfast about why the border was closing. But if I decided I needed to leave, I would need to pay him. If I decided to stay, I would need bolivianos – perhaps enough to last me through Bolivia, as my rural route surely would not pass any banks.

The first ATM I went to didn’t work. The second had a locked door. The third told me that there wasn’t any cash available.

As I looked for another bank on my phone, a man approached me in the plaza.

“¿Qué buscas?” he asked.

“Un cajero que funciona,” I told him.

“No hay,” he chuckled. “No hay plata.”

He told me what I had begun to suspect. There was no ATM that worked. There was no cash. Whether due to the roadblocks limiting supply, or banks’ reticence to allow a run on cash in the midst of a crisis, I wasn’t sure. But I wouldn’t be able to withdraw any bolivianos this morning in Copacabana.

“¿De dónde eres?” The man asked. I could smell alcohol on him, as he wobbled a step toward me. But somehow I could tell, either by his friendly composure or his clean, neatly ironed clothes, that wandering the plaza drunk at 6am wasn’t normal for him.

“Los Estados Unidos.”

“The United States,” he repeated slowly. “Nice to meet you. My name… is Javier.”

“Mucho gusto,” I told him.

“My friend,” as he put his arm around me, “Bolivia, we have, problemas, problems. Está muy malo. Bolivia está malo.”

“Yo sé.”

“I lived…in Houston. Very nice.”

“¿Si? Mi hermano vive en Houston.”

“Houston is good. Bolivia, muy malo.”

“Si – espero que todo mejora, pronto.”

We chatted a bit, but I soon left him in the plaza. I felt bad, but I had to get back to the hotel. The cash shortage had made my decision easy. If I couldn’t get cash, I couldn’t get through Bolivia. If there were cash shortages, there may also be food shortages. The road blocks shut down local economies, on which I rely completely. I would have to go back to Perú.

~

Maurice didn’t have much more detail at breakfast. He repeated what he had said the previous night, that he didn’t know why, but that the border would close, while he ran back and forth across the dining room serving eggs and bread and coffee to a full house. Everyone in the hotel was awake and ready to leave on a bus that morning. I texted Noel and Carolyn, who were staying at a different hotel — “They say the border is closing. I am going back to Perú.” The text was a complete reversal of the confidence I’d expressed to them about my rural route the night before.

On the ride back to the border, I went around some logs strewn across the road. I didn’t think much of it, but at the border, I learned a little more from a local tour guide who was ushering his clients out of the country. The mayor of a neighboring town, one that is significantly poorer than Copacabana, had told the border agent to close their offices in the morning, and that they would block the road into Perú. The border agent was friends with Maurice and had called late last night to advise him to get his guests out.

The agent gave me a stamp back into Perú, and a rush of relief. “Mejor para salir,” the tour guide reassured me, as he boarded his bus with his clients and I got back onto my bicycle. For the first time on my trip, I didn’t really know where I was biking to, just that I was leaving Bolivia.

~

Post script: I recognize that this piece is a little self-centered and lacking in the political analysis that both sides of this conflict deserve. My challenge in writing this, as a personal blog, is to convey my own experience. In this case, I could go on for many more pages talking about the history and complicated positions of both sides, and I wish I could, but I will leave it to journalists who are more qualified than I to cover that aspect. Many people I spoke to in the US had no idea of the conflicts happening in Bolivia, or Chile, because the US media was caught up in the impeachment hearings at the time. I encourage you to learn more about what is happening to our neighbors – here is a link to a good starter article on Bolivia.

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||