¿Dónde está Pablo?

Colombia“Me llamo Pablo,” our tour guide told us, in slow, enunciated syllables, so that the gringos in the “Basico Uno” class could follow. “Como, Pablo Picasso, o Pablo Neruda.”

He was omitting another Pablo. One which us gringos would think would be the first to come to mind in this city, but whom our Pablo deemed unworthy to mention in the same sentence as an artist and a poet.

In our orientation on the first day of español classes, the coordinator surprised us with an astounding fact about the school, which hadn’t been advertised on their website, reviews, or anywhere: “Pablo Escobar was killed in this building. Because of that, you will see many tourists stop to take photos outside the building. We want you to be aware of this, but as a school, we prefer to focus on the future, not on the past.” A school for foreign tourists in the house where they eradicated the terrorist that held the city and country hostage for years – what perfect symbolism. And just like that, Escobar faded into history.

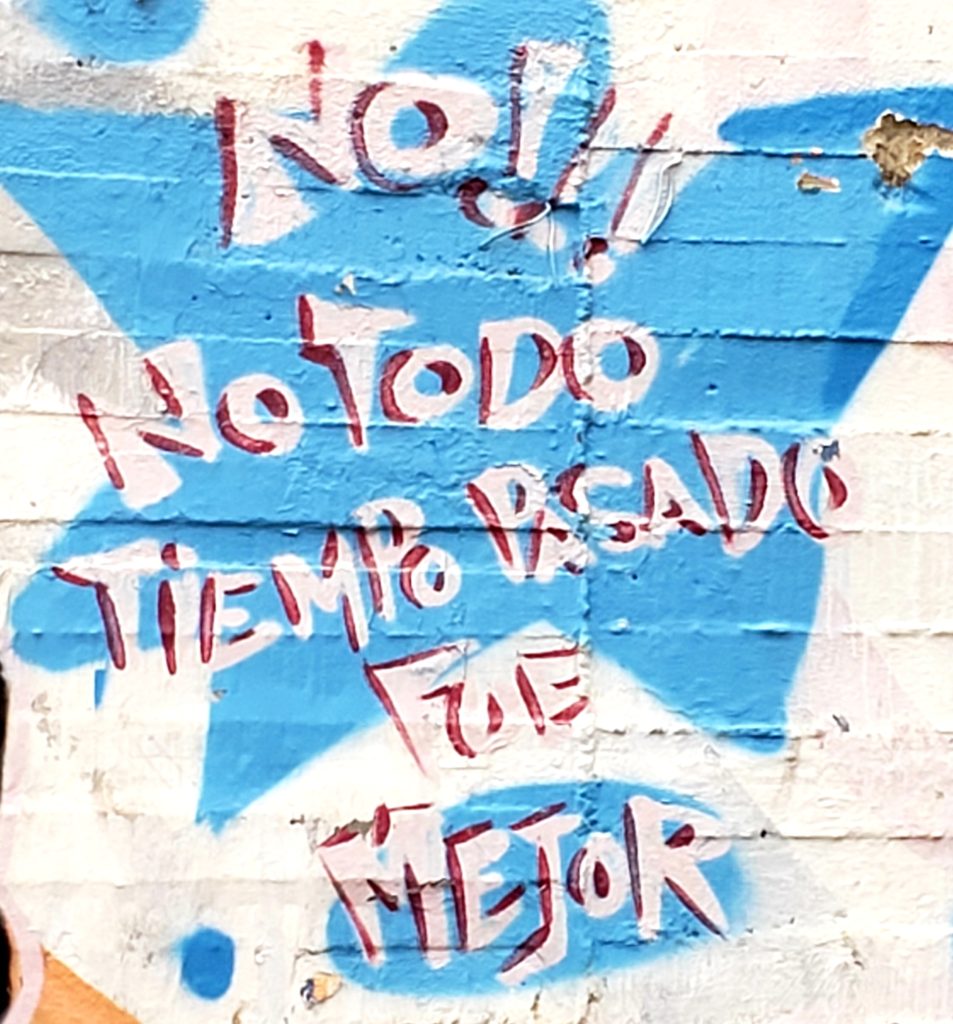

Rather, our time in Medellín, which revolved around the programs of our school (Colombia Immersion) and Liz’s salsa classes, focused on what the city has become, not its tragic and violent history. At every turn, the message was that of pride and optimism, not of regret or loss.

The school partnered with Pablo (Real City Tours) to do a “field trip” each Thursday that showcased a barrio in the city that has benefited from transformation. In each case, we visited a neighborhood that tourists rarely see, areas that had once been the worst of the worst, but via infrastructure investment and public programs, have become fountains of promise.

In Moravia, residents had once squatted on top of a toxic, illegal landfill, which the city has now vacated and turned into a beautiful public park. We toured a greenhouse in the park that was established by former women residents for the purpose of mentoring young women botanists in entrepreneurship.

In El Cinturon Verde, the city erected a beautiful public park, with hiking trails, gardens, and art displays, all on the top of a mountain, in order to stop the upward growth of the city by squatters. In Medellín (as in many Latin American cities), the poorest of the poor live up in the suburban heights of the mountains. The parks provided recreation, beauty, and employment to this community while also giving the residents pride in their real property and surroundings, which further helps to combat unregulated expansion.

In Manrique, we saw how the public utility company EPM has established community centers alongside their hydroelectric power plants, free to the public, with workshops, recreational classes, and other programs, for the purpose of creating an involved and educated citizenship. “¿Que programa es su favorita?” Pablo asked two young girls who were following us around on the tour. “Baile!” Dancing, they said. Their least favorite was reading. At least it was offered!

In Treize de Noviembre, Pablo explained how public infrastructure in the form of better streets, pathways, lighting, parks, schools, and community centers had helped cease a problem known as “las fronteras invisibles.” Gangs used to harass or even murder innocent citizens that had unwittingly wandered into the wrong territory. While their presence in the city has been heavy, and inarguably necessary, the army and the police cannot create progress or eradicate the culture of crime, Pablo told us. Only infrastructure and community can do that.

As a result of Medellín’s transformation, we were able to experience the beauty of its culture, without dwelling on the demons of its past.

We learned salsa at a dance school, Estilo Cubano, and practiced at a nightclub, Son Havana, known for the best dancers in the city. Or, I should say, Liz danced salsa and I desperately tried not to embarrass her by tripping on myself or bumping the professionals.

We bought fresh fruit and meat from the local mercados and the vendors walking through the neighborhood with carts of produce, instead of grocery stores. We dined on the ubiquitous, cheap, and delicious menu del día. The menu del día is a set menu at nearly every restaurant that provides an economic option for the average worker, complete with soup, rice, salad, meat, slices of platano or yuca, and fresh juice, all for 10-12 mil pesos ($3-4). You don’t get to choose, but I was never disappointed.

We played fútbol with niños in the rain, on concrete courts that left me with bruises for days as I slipped left and right chasing the kids around. We tossed metal balls toward targets filled with gunpowder in the Colombian game of tejo – similar in concept to the American games of cornhole or horseshoes, but add the thrill of an explosion when you hit the target.

We made friends through a Friday night language exchange, which brought us students together with locals looking to improve their English over “polas” (the informal Colombian word for cervezas, like “brewskies”). Every Friday, I’d toss a few polas back with the same people, but I could speak to them a little bit more competently each time.

We used the city’s immaculate and efficient metro systems, which make San Francisco’s BART and New York’s subway trains seem like filthy relics of the 20th century. We rode up cable cars that linked the metro to the heights of the mountaintops. We took buses that navigated seemingly impossible pitches and pinches to reach farflung barrios.

We even wandered through Medellín’s massive, packed, and gloriously air conditioned malls. While I’m not typically the person to visit a mall on vacation, I found the malls oddly comforting and appealing in their luxury, here in a city that so many Americans might think of as third world.

When Liz returned to her the US for her public policy program and told people she’d spent a month studying salsa and Spanish in Colombia, another student in the program asked her, “Oh, so you weren’t there helping people?” After all our experience seeing the rapid progress of government programs, the proficiency of Medellín’s commercial sector, and the vibrancy of its culture, the thought of an American student doing something to “help” the people of Medellín – by what, teaching them the ways of America? – seemed outright laughable.

We learned to love the city for what it is and not what it was. On a vacation of 3 or 4 days or even a week, you can learn about the history of a city, appreciate it, and move on. But I found that it took all of our month in Medellín to really embrace what it is today. I completely missed many of the main tourist attractions, like Comuna 13, Parque Arví, Casa de Memorias, and the infamous La Catedral. But I felt like I came away with a bond to the city much deeper than I ever have in a city that I blitzed from museums to parks to monuments to fancy restaurants.

When I returned to Medellin, I stayed in the expat heavy zona rosa of El Poblado, instead of Laureles, where Liz and I had lived. Laureles was an upscale but much more local barrio than El Poblado. After six days of biking through smaller towns and only encountering one person who spoke English, I was craving the luxury and the English speakers that El Poblado offered. El Poblado delivered on these fronts – but meeting other Americans and learning about their experience Medellín via the lens of El Poblado, I realized how much different my experience had been. El Poblado replaced salsa and bachata with house and reggaeton, replaced the menu del día with fine dining, replaced the fruit carts with hustlers hawking weed, coke, and bubblegum, and even the Colombians who worked in the neighborhood insisted on speaking to me in English. And I became painfully aware that for the rest of my trip, I won’t get another experience like Medellín. Even in layovers of several days or a week, I’ll be rushing through the tourist sites, introducing myself to people halfheartedly, knowing I won’t ever see them again. I realized that I will be in no place to judge any city by two or three quick days; that scenic viewpoints, trendy cafes, and top TripAdvisor “things to do” don’t teach you how a city lives and breathes. All which made me appreciate the time I had with Liz in Medellín even more. Me encanta, Medellín. ¡Volveré pronto!

1 comment

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Love reading about all! You spin a wonderful story with great pics!