El reincio del viaje

ChileIn its very initial concept, this bike ride was only meant to go through Chile. I visited Chile in 2015, but only had four days to spend before meeting friends on the Argentine side of Patagonia. What can I do with four days in Chile? I thought. Very little, I soon learned! The Atacama desert, the high Andes, Patagonian fjords, thousands of miles of beautiful coastline — Chile turned out to be way bigger than I had thought! But it looks so skinny on the map — a thought which compelled me to think, long before I knew about the sport of “bike touring”: I’ll bet I could ride a bike down the whole thing and see it all!

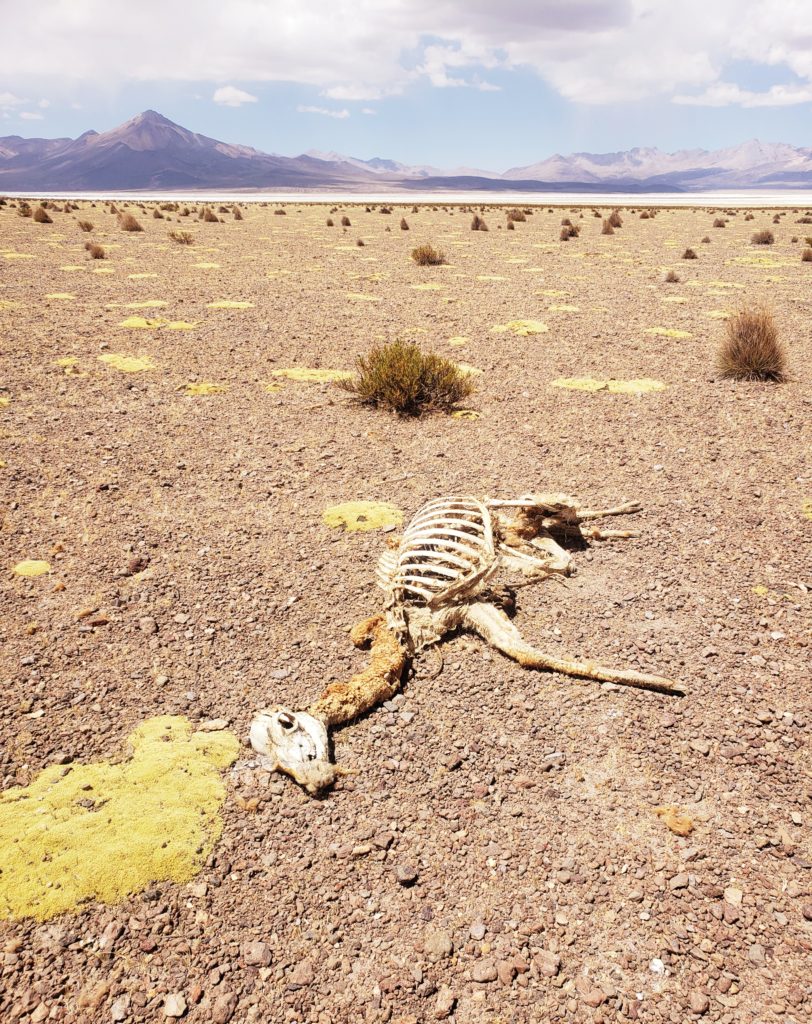

When I decided last year that I needed to take some time off and started researching what a Chilean bike traverse might look like, I supposed I should start at the north end. Zooming in on Google maps, I found the furthest north town in the country, called Putre. To my excitement, Putre happened to be the gateway to a national park! I found jaw-dropping pictures of Parque Nacional Lauca, with snowy volcanoes and wildlife. But as I measured miles along roads, I didn’t find too many other settlements. In fact, the entire area looked like an uninhabited desert for a long way south of Putre. Despite the intriguing scenery, this region hardly seemed like an acceptable place to start my first ever bike tour.

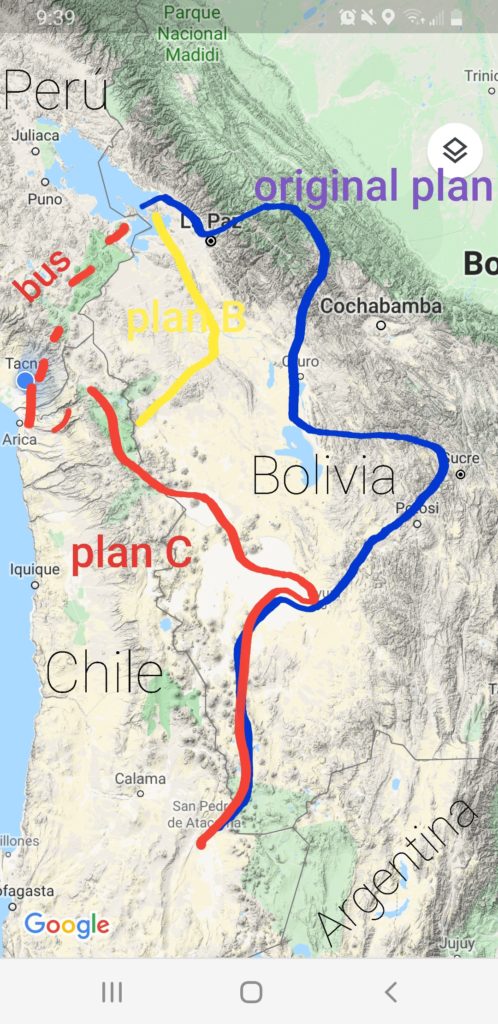

Then I started looking at bicycle touring blogs and realized that most people biking through Chile came first through Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni, the largest salt flat in the world. Whoa! I couldn’t miss that! Reading backwards, I learned that most of them had come to Uyuni from La Paz, the highest altitude capital city in the world, at the base of an incredible mountain range. And La Paz wasn’t far from Machu Picchu, which I couldn’t miss if I was in the area… Pretty soon, the little two-month itinerary across Chile became a cross-continental monstrosity and I totally forgot about Putre and Parque Nacional Lauca.

Holly reminded me about the area when we rode together in southern Perú. She planned to ride a bikepacking route that someone had documented online, starting in Putre. Beyond directions, this website included recommendations for water sources, food supply, campsites, road conditions, and the locations of several natural hot springs and flamingo viewpoints. Though I hadn’t seen this site in my initial research, I recalled with excitement the pictures I had uncovered.

“Awesome!” I told her. “I’ve got different plans though…I’m going through Bolivia.”

A few weeks later, I escaped Bolivia in desperate need of a plan and inspiration to resurrect my bike trip. I texted Holly, “Are you still going to Putre?”

Not only did I crave some company on the road, but I thought I could learn a thing or two from Holly. She has much more experience bike touring and operates with a self-reliance that I envy, camping and cooking for herself far more frequently and competently than I. Even though I’d been in some remote places in Ecuador and Perú, I still hadn’t ridden for more than two days without being able to buy food in a restaurant or store. The Putre route would require at least four days of self-sufficiency. In the remote desert of northeastern Chile, I felt I would be much more comfortable riding with Holly than alone.

Holly didn’t respond to my text, which wasn’t surprising because she was likely biking through the middle of nowhere. But I counted the days since I last saw her and figured she should be approaching Arica — the only legal border crossing between Perú and Chile and the only way for us both to continue southward without going through Bolivia.

So, in a whirlwind of impulsive decisions and coincidental timing, only thirty minutes after re-entering Perú from Bolivia, I found myself stuffing my bike into the luggage compartment of a bus for the first time of the trip. The next day, I was eating avocados with Holly in a hostel in Arica, Chile, staring at that same map of desolate roads in Parque Nacional Lauca that I’d scoured when I first daydreamed my South American bike ride.

Locationally, Putre made a logical place to restart the engines, just on the Chilean side of a three-way border with Bolivia and Perú. The town sat at a similar elevation to where I’d hopped on the bus in Perú, about 12,000’. I had worked hard biking uphill to earn that elevation! So I rationalized that taking a bus back up into the mountains would be fair. It would really be as if I had just teleported across a small section of Bolivia, rather than bussing all the way down to the coast and back.

Additionally, we had heard reports that tours were still operating in the famous salt flats near Uyuni, Bolivia. Apparently, the political crisis and protests had not impacted the remote southwest corner of the country. With any luck, we might be able to safely bridge our route in northeastern Chile to the salt flats of Bolivia — what had been a highly anticipated part of both of our bike journeys.

And so it happened that, after another uncomfortable bus trip, my bike trip resurrected itself in Putre, the same little town where I initially thought I might start the whole thing.

By the end of the first day of pedaling, Holly and I had both already benefited from each other’s presence. We passed a little shack of a restaurant around lunchtime, and I proposed that we stop to eat since it would be the last food we’d see for several days. With much logic, Holly pointed out that we were both weighed down with five days worth of food — we should probably start eating some of it! So we stopped at an overlook and watched moody clouds circle the mountaintops, while I stuffed two giant tortillas full of salami, cheese, avocado, and tomato. I pondered why I am usually so predisposed to rely on roadside restaurants — the sack lunch strategy was so much more fulfilling!

After lunch, I succeeded in convincing Holly to take a sidetrack to see the Iglesia de Parinacota, a tiny Jesuit chapel in a nearly abandoned town, thought to be the oldest church in the country. Holly reluctantly agreed; she rarely deviates from her route to see tourist attractions. But when we got there, she led the way through a tunnel of a staircase so narrow that we kept bike helmets on for safety and emerged in a belltower where we could look out over the quiet huddle of huts surrounding the church and the desert beyond them. “This is really cool. I probably would have never come here on my own,” she said.

We set up camp later in front of Lago Chungará, a stunning blue lake at 15,000’ with a backdrop of snow-capped volcanoes. I would later see the same exact view from our campsite on a billboard in Santiago’s subway, advertising the national park system. And yet, we had the place all to ourselves.

That is, until after the sun had gone down, while we were cooking dinner, when we saw a single headlight pulling into the campsite. It was a bicycle!

“I haven’t seen any bicyclists in at least a month!” Rosanna exclaimed with an emotional English accent. “And then today, I ran into two Colombians, and now you two!”

I had been nearly ready to doze off to sleep and could hardly follow the newcomer’s excitement as she told us that she had just come from the nearby border with Bolivia. She complained that the Chilean border agents wouldn’t let her through the border alone; that she had to be in a minimum group of three. She waited at the border and to her luck, several hours later, two Colombian cyclists showed up and they passed through the border together. The Colombians lagged behind and would show up later in the evening.

“But you were in Bolivia? How did you get through Bolivia?” I asked.

“It was AWFUL.” She had left Copacabana several days earlier and taken a very similar route to the one I had planned, passing through many roadblocks. She encountered friendly people at the earlier roadblocks, nearer to La Paz, but the more rural she went, the more aggressive the protestors became. In several instances, men and children surrounded her, trying to take things from her bike as she yelled at them to stay back. Roadblocks had been more frequent than even the map I’d seen indicated. In fact, at the border, Rosanna had been asked by the Bolivian army about the location of protests, since she had passed through places they couldn’t access. “I’m just glad I got out of there alive,” she said.

“Wow,” I said. “I was in Copacabana a few days ago too. But after talking to people, I decided not to continue. What did people tell you?”

“Oh, I didn’t ask anyone,” she said.

“You didn’t ask anyone?”

“No, I’ve learned that when you ask people if something’s safe in South America, they always say it’s not safe, especially for women. So what’s the point?”

I shrugged, a little speechless. Had she even been aware of the political situation? I didn’t ask.

As I settled into my tent, the stress from Copacabana strangely resurfaced. From a logical standpoint, Rosanna’s horror story and limited diligence completely justified my decision to bypass Bolivia. But a little voice I couldn’t silent screamed at me: “She went through Bolivia and made it! And you ran away!” Could I have made it? Could I have had an incredible adventure story to tell? I stared across the lake to the Bolivian volcanoes on the other side, lit up by the moonlight, wondering if I had made the right choice.

Rosanna had intended on biking to Putre to resupply food, but, eager for company, she decided to join us after we offered to share some of our food. “I don’t eat much at altitude anyway,” she said.

In the morning, we set off south, a team of three. Or rather, Holly and Rosanna set off south about an hour before I did. They were ready to ride while I was still sipping my coffee and watching flamingos strut across the lake, my tent and gear still in shambles.

“He’s fast, he’ll catch up,” Holly said as they biked away. I caught up to them later that morning, but only because they were relaxing at a natural hot springs in the middle of the desert. This order of events became a routine over the next several days. I never became capable of getting my act together in the morning, and they always found some hot springs to relax in while waiting for me.

I dipped my feet in one of the steaming geothermal puddles, looking out over a vast white salt flat, toward the mountains that formed the Bolivian border beyond. I’m glad I’m not over there, I realized. A few days ago, I had been defeated by Bolivia, almost ready to fly home, and now I’m somehow biking with two new friends through striking desert landscapes, swimming in hot springs between snowy volcanoes. Things worked out pretty well, even if I did have to take a bus.

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |