La minga y la mita

Perú“Se llama ‘el Machu Picchu del norte,’ pero es muy diferente,” the tour guide told us.

We were standing in a ruined fortress on top of a mountain, called Kuélap. The tourist industry compares it to Machu Picchu in order to draw more visitors to this remote area of northern Perú. That was enough to put it on my itinerary before I started the trip. I didn’t do much research, so I assumed it was an Inca site. Aren’t all Peruvian ruins from the Incas? I had thought. I knew the Inca empire was one of the world’s great ancient civilizations, so hadn’t thought twice about the possibility that there were other pre-Columbian cultures of any importance in Perú. I had also pictured the Incas as a peaceful, benevolent indigenous people, unjustly conquered by the Spanish conquest in a classic conflict of colonial cruelty.

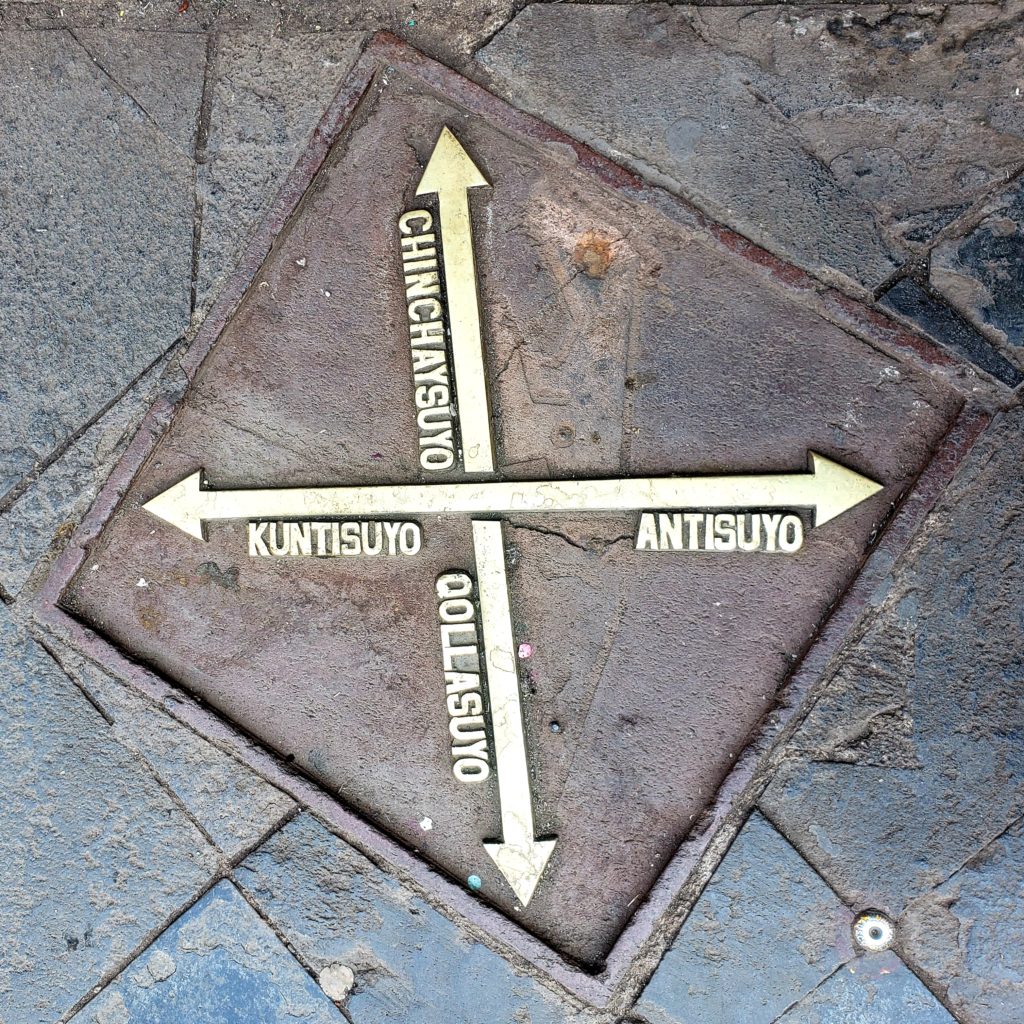

As I traveled south through Ecuador, or the part of the Inca kingdom called Chinchaysuyu, the Incas were spoken of in the same breath as the Spanish. The Otavalos, the Quitus, the Cañaris — all had similar stories. Cultures with long histories and rich traditions sadly conquered twice in the span of fifty years — first by the Incas, then by the Spanish. In some cases, I learned that the Incas would forcibly relocate the conquered populations, uprooting them as a way to destroy unique identity and assimilate populations into Inca culture. The Incas’ subjugation could be so intolerable that some peoples, such as the Cañaris, opted to fight alongside the Spanish during their conquest, hoping to exact revenge on their first conquerors. Sure didn’t sound like the harmonious society I’d envisioned.

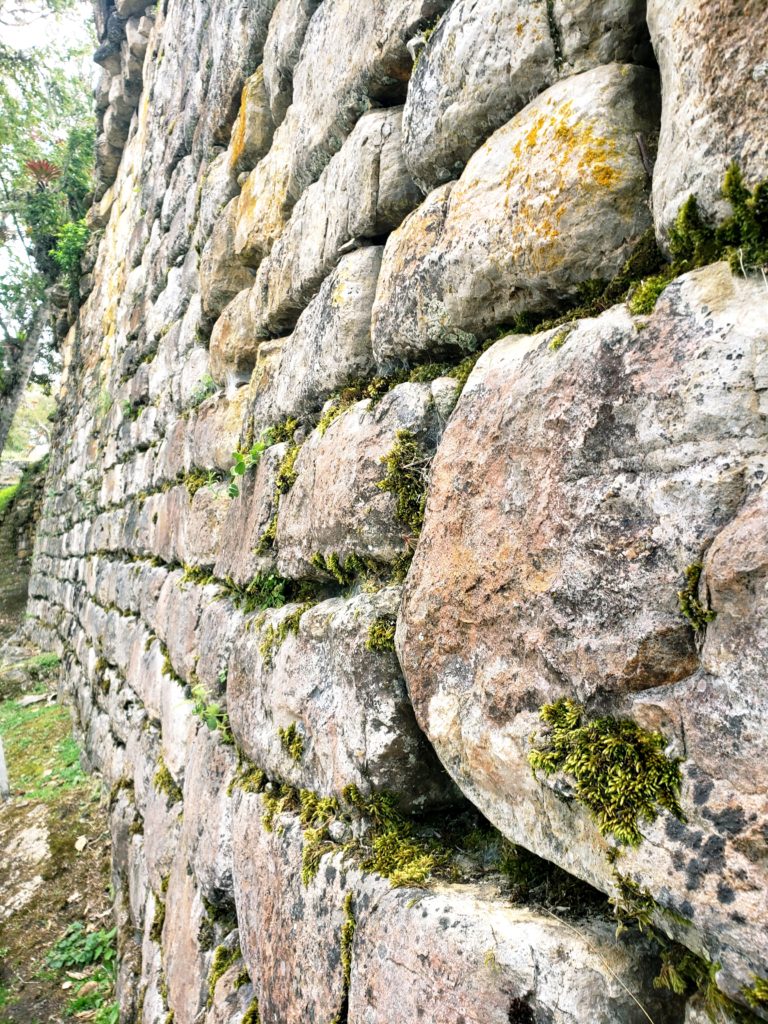

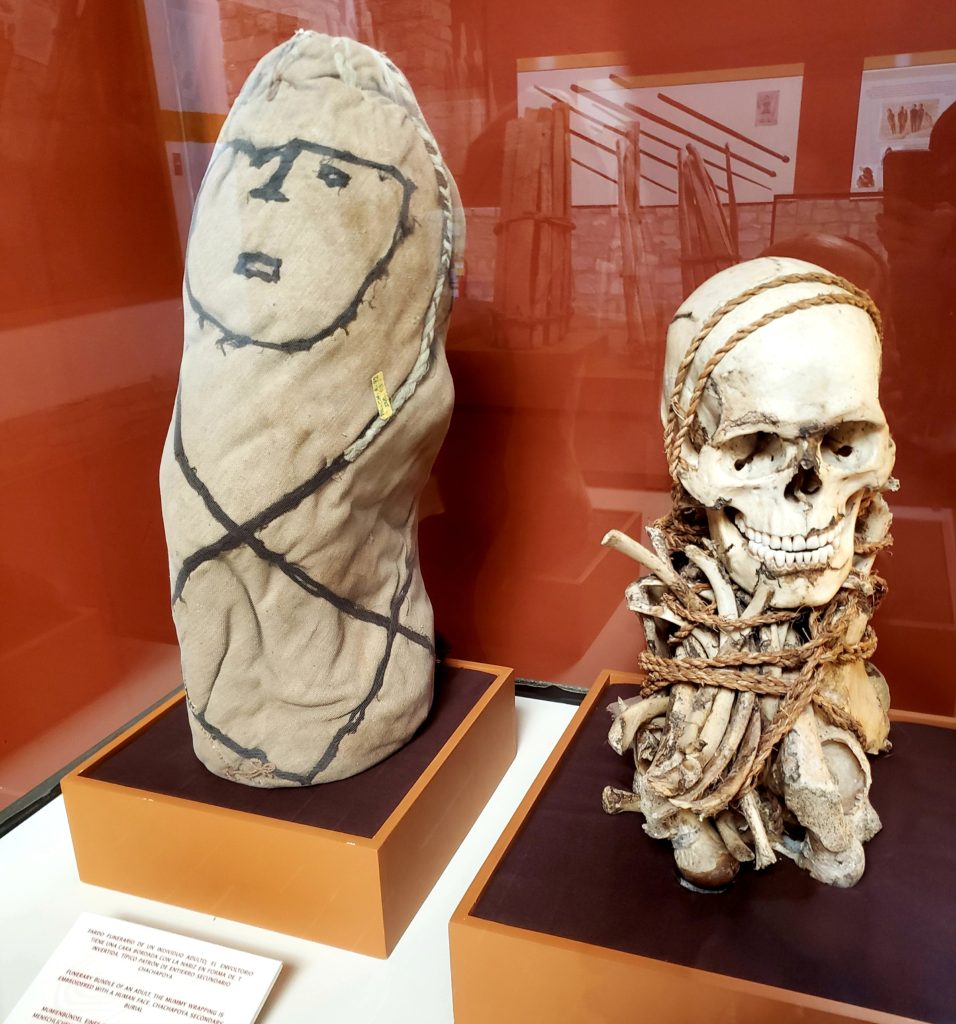

Our guide at Kuélap described a similar series of events that occurred on the mountain on top of which we stood. The Chachapoyas people built the stone city around 400 AD, and it thrived for over a thousand years, before the Incas besieged and conquered it in the 15th century. The Incas then presided over Kuélap for only fifty years before the Spanish arrived, capturing and killing the Inca emperor in nearby Cajamarca. In the ensuing wars, the Chachapoyas, like the Cañaris, sided with the Spanish. Perhaps too wistfully, they hoped to be liberated from Inca oppression.

Meanwhile, he explained, the famed Inca city of Machu Picchu thrived for only about fifty years from its commission to its abandonment, when the Incas fled Spanish incursion by escaping into the jungles. As I stared at the rings of stone in which the Chachapoyans had lived, I tried to contextualize those lengths of time. Machu Picchu stood for only fifty years – I couldn’t think of any contemporary cities that young. Kuélap stood for a thousand years – I couldn’t even get my head around that epoch.

“Pero la diferencia la más importante,” our guide continued, “es entre la minga y la mita.”

Kuélap had been built on the concept of “la minga,” or community organizing. When someone in the village needed something built, fixed, or solved, the whole community chipped in to help. Machu Picchu, as well as the rest of the Inca kingdom, had been built on the concept of “la mita,” or forced labor from the peasant class. Our guide equated la mita with slavery, although many historians describe it as a tax burden on conquered populations.

Coincidentally, I ended up visiting Machu Picchu, the legendary city built by la mita, only a week after touring Kuélap. Liz had flown down to Perú to visit, so I left my bike in Chachapoyas for some much needed vacation time in Lima and Cusco.

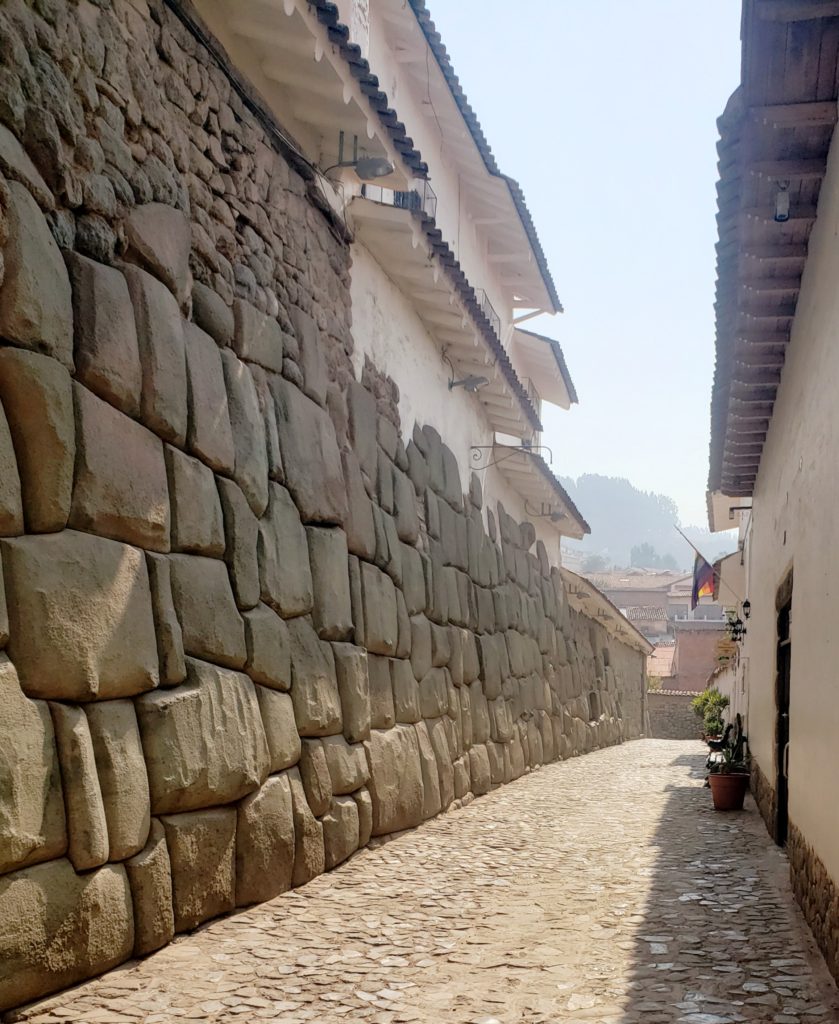

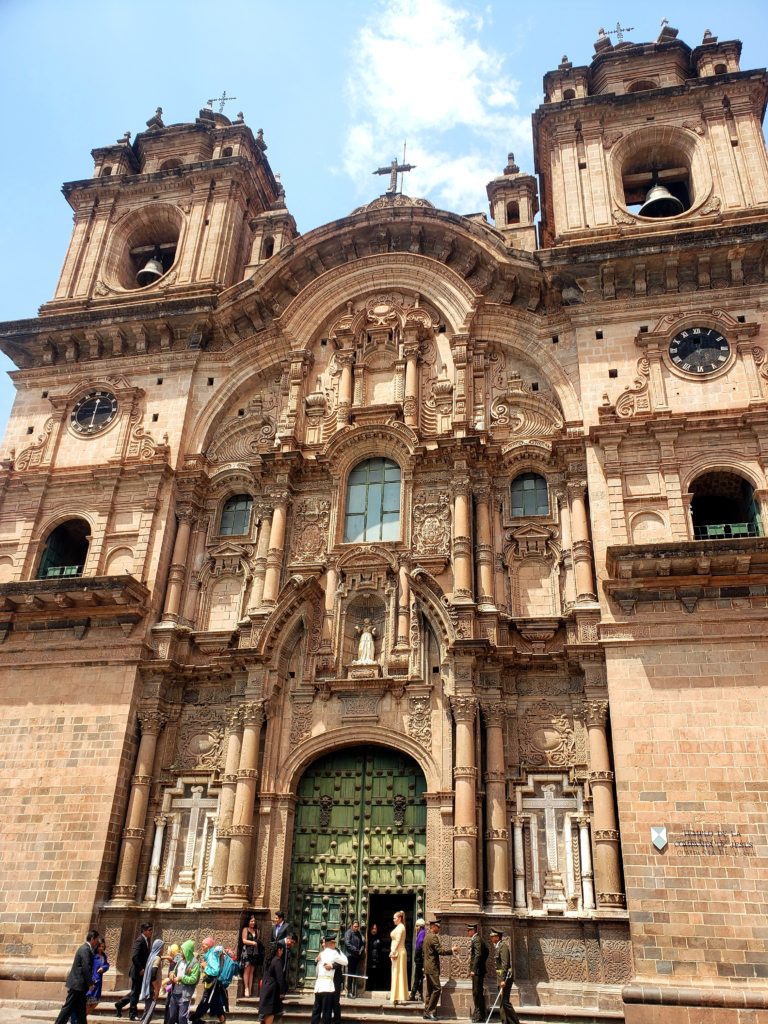

The city of Cusco offered a new perspective on the Incas. Magnificent stone architecture, people dressed in colorful Incan costume, and even a reenacted parade of warriors carrying their emperor on a royal litter. Here, the Incas were venerated, rather than resented.

Even the Spanish brutality was downplayed in Cusco, the tourist capital of Perú. A tour guide told us, “Cusco was founded twice. First, by the Incas, then again by the Spanish.” Founded for the second time? That seemed like a pretty soft way to characterize the theft, slaughter, and manipulation that led to the conquistadors’ occupation of the Inca capital. Just that morning, before the tour, Liz and I had observed how the Spanish built their Catholic cathedral right on top of the Inca’s most revered temple, Coricancha – after stripping it of all its gold and silver decoration, of course.

Descending from the mountains to the jungle on the train to Machu Picchu, Liz asked me, “so – do you know anything about the significance of Machu Picchu to the Incas?”

I thought for a moment. “No, not really.” I was a little embarrassed.

As we strolled through the stone walls of the ruined city, we asked the tour guide that same question – what was the story behind how Machu Picchu ended up on this remote jungle ridge top? She replied with a barrage of irrelevant facts, about how the American explorer H.R. Bingham discovered it in 1911, about the state of its present day restoration, and about the religious and astronomical significance of some of its buildings. I left Machu Picchu blown away by its beauty, but with little more knowledge than when I arrived.

I later read that historians believe Machu Picchu actually served as a country estate for the Inca nobility vacationing from Cusco. Recalling the wondrous jigsaw of massive stone bricks, I couldn’t help but think of the laborers that must have tired to build this city, solely for their emperor’s indulgence. Slavery or tax burden? Maybe somewhere in between, I thought.

In the movie The Motorcycle Diaries, a young Che Guevara visits Machu Picchu and writes, “The Incas knew astronomy, brain surgery, mathematics, among other things. But the Spanish invaders had gunpowder. What would America look like today if things had been different?… How is it possible to feel nostalgia for a world I never knew? How can a civilization that built this (Machu Picchu) be destroyed to build this (Lima)?” *

Of course, while standing amidst the architectural and natural beauty of Machu Picchu, I also felt nostalgia for a lost civilization. This precise sentiment draws millions of visitors to Machu Picchu each year, despite its relative unimportance within Inca history. But, though the misty, terraced mountains and beautiful stonework may inspire many idyllic visions of the past, the Inca legacy isn’t quite as pretty as its terraced cities. Superior architecture and natural beauty doesn’t correlate to political justness of a society. While the Spanish conquistadors were undeniably brutal, the Inca empire does not appear to have treated its subjects any better than the average 16th century kingdom. What would America look like today if the Incas had fended off the Spanish? It’s an interesting thought, but perhaps that nostalgia is not worthy of inclusion as an inspiration for the indigenous revolution that Che and his compañero Alberto discuss as they sit on the terraces of Machu Picchu.

As I continue to trace Inca roads on my bicycle, south through the former Inca kingdom of Tahuantinsuyu, I’ll surely learn much more about the Incas, the Spanish conquest, and the narratives that captivate much of Peruvian history and literature. But amidst the lore of the Inca kings, I hope not to lose sight of places like Kuélap that existed peacefully for many years before the brief Inca dynasty conquered the historian’s spotlight.

–

* I have also read Che’s actual diaries, which do not contain these quotes. I don’t know where they came from, but I assume that the screenwriters did sufficient historical research to fairly paraphrase Che’s beliefs.

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |