Las ligas mayores, cápitulo dos

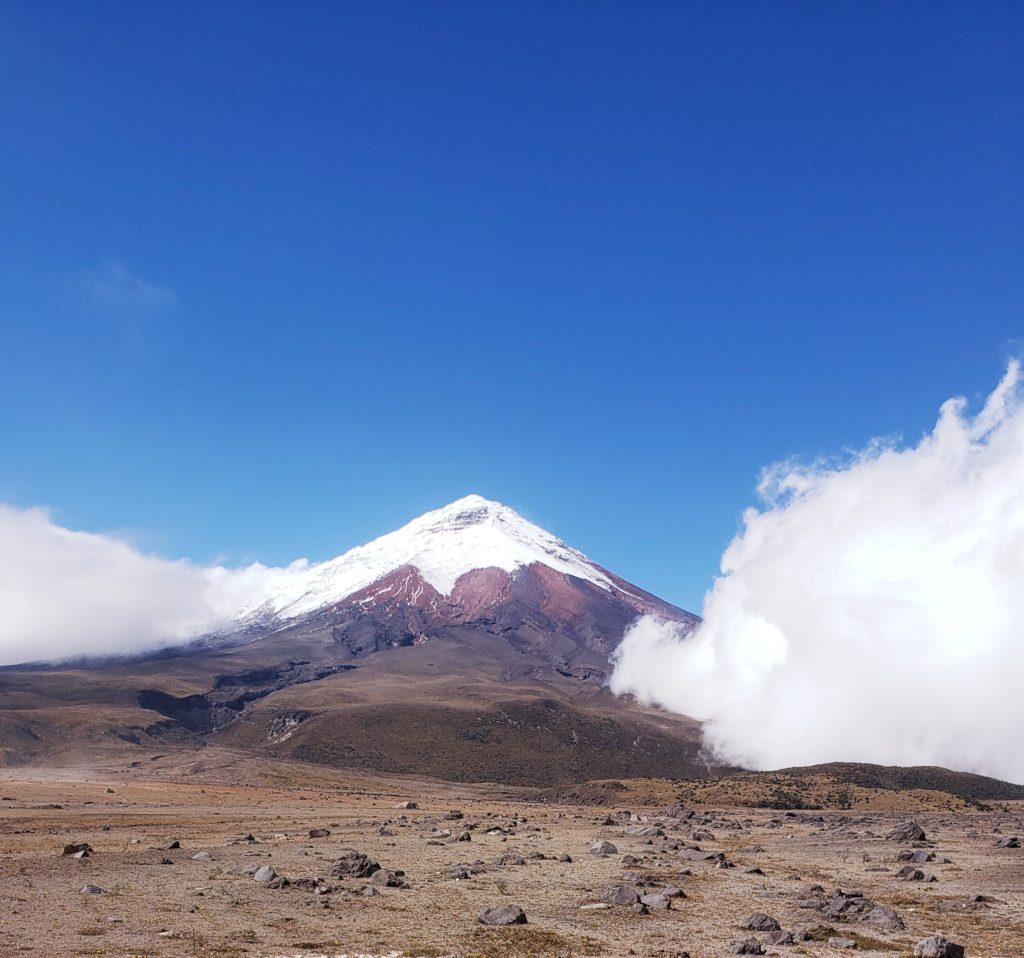

EcuadorWith a new chain installed, dry bags protecting everything inside my bike bags, warmer clothes, a lighter, a backup lighter, and many hours of sleep, I felt I might be ready for another shot at the big leagues. From Quito, I aimed to reach the iconic triangular volcano of Cotopaxi, a notoriously shy mountain that spends most of its days hidden in clouds. I planned to camp somewhere near the volcano – not sure where, but hopefully, I would be prepared this time.

A few miles outside of town, I ran into a few cyclists stopped on the side of the cobblestone road, trying to fix a flat tire. “¿Necesitan algo?” I asked.

“¿Tiene una bomba?” I pulled out my pump and he tried inflating the tire but the air hissed out of a puncture.

“Hay un pincho,” I told them, “no tiene otro neumático?” The two other riders both had extra tubes, but they were 26” in diameter. The guy with a flat needed a 29” tube. I told him I had one if he needed it, but that we should try to patch the punctures first since I was headed places that replacement 29″ tubes aren’t available for sale. We found two punctures in a fang toothed pattern indicating that the tube had been pinched between the tire and the rim on both sides, called a “pinch flat.”

“No tenía suficiente presión en la llanta,” I told him. Riding on the cobblestones, tire pressure makes all the difference. With tubeless tires, I’m able to use a low tire pressure, effectively giving me a bit of suspension to absorb the bumpy impact. But using a low pressure with tubes, he was asking for a pinch flat. Another pair of patches on the same tube indicated a similar pattern of mistake. “Deberías comprar llantas tubeless para las rutas empedradas,” I advised him.

“Si, pero tubeless es muy caro,” he complained.

“Tan caro que muchos neumáticos nuevos?” My eternal justification for expensive gear – that the cost of replacing cheap gear eventually catches up to the cost of the good stuff. He shrugged. He was considering it, I think. He thanked me and they sped off.

I never saw Cotopaxi that day before finding a camp somewhere below it, in the national park. The wind howled as I finished setting up camp in the dark. As I started cooking, some voices startled me. I had been following a remote trail through the park for hours and hadn’t seen anyone. Two headlamps came into my clearing.

“Estamos perdidos,” they told me. They wore helmets and backpacks and looked completely flustered and distraught. They explained that they had been climbing a mountain nearby. Caught in fog, wind, and rain, they had lost the rest of their group and were now looking for the rendez-vous at the entrance to the national park.

“Tengo un mapa en mi celular,” I told them as I took out my phone. I didn’t know where we were in relation to where they came from or where they wanted to go, but at least I was prepared with several different offline topo maps. The man, Pedro, studied them and took some photos.

“¡Que día terrible!” Diana, the woman, exclaimed while she tried to dry her jacket in the inconsequential warmth of my cooking stove.

“¿No tienes miedo acampando aquí?” Pedro asked. I was surprised that he should ask if I was scared, when he was the one wandering lost in the dark.

“No. ¿Debería?”

“No,” he said, rationality filtering back into his flushed face. Nothing around for miles and miles – what would I be afraid of?

Pedro finished with the maps and urged Diana to get up. “Solo treinta minutos mas,” he told her.

“Si no lo encuentran – vuelve, tengo comida,” I invited them as they wandered into the darkness. They didn’t come back, so I assumed they must have found their group.

As I finished cooking, feasted, and settled into my dry, warm sleeping bag, I thought back to Laguna Mojanda. Sure, that had been an uncomfortable night, cold and hungry, but I had survived. The cyclist earlier today wasn’t properly prepared with a spare tube, but he survived. The mountaineers this evening weren’t properly prepared with maps, but they would survive – I hoped.

Was I ready for the big leagues? Maybe, maybe not. If not, I’ll survive. And be better prepared the next time.

When I awoke in the morning, the clouds had cleared and Cotopaxi loomed over the barren, volcanic moonscape in its full glory. I crawled my way up to the 13,000 foot pass at the mountain’s foot over faint jeep trails, alone with the sun and the breeze and a pale green mat of lichen. Feels good to be in the big leagues, I thought. Ready or not.

1 comment

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Your pictures are breathtaking!!! Wow!! Can’t wait to show Mr. Joseph!! Glad all is going well!

Xmary