Más empleo, menos montaña

Perú“Ah, San Francisco,” the manager at Hotel El Minero said knowingly as he looked at my passport. “Una familia de Oyón vive allá.”

“¿En California?” I asked incredulously. Oyón is deep in the Andes, one of the poorest regions of Perú. Only the wealthiest of andinos I’d met could even think about affording transportation to California, much less living there.

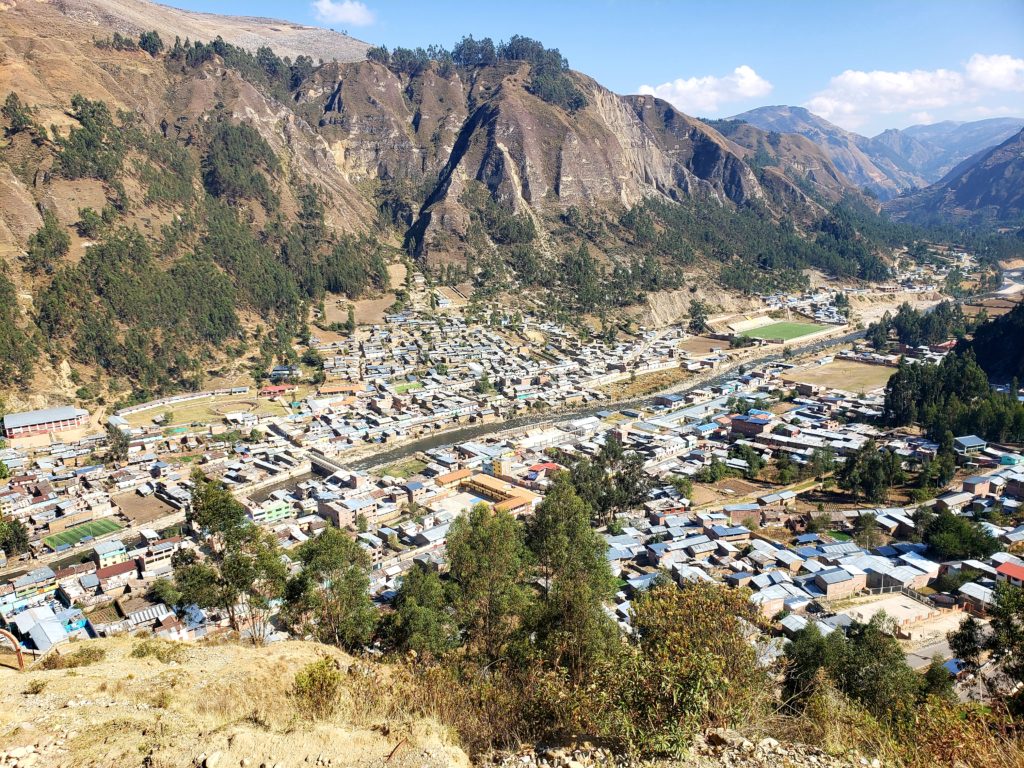

“Si, pero hay algunas otras viviendo en Nueva York,” he said proudly. New York too? Oyón didn’t strike me as anything special from my bike. It looked just like every other small city in the peruana sierra. Dusty streets, shabby concrete buildings with clay tile roofs, and few aesthetic touches apart from some gardens in the Plaza de Armas.

I watched a bus park in the Plaza and unload a troop of young men in filthy orange and blue jumpsuits. They marched single-file, like ants, to form a line for the one ATM in town. Then I made the connection — the money is from the mines.

Mining has long been one of the most important industries in Perú, but its economic role has been particularly important in the 21st century. According to a report by the accounting firm EY, in 2018, mining represented 10% of Peruvian GDP and 60% of exports, and the industry has driven an overall economic boom that cut Peru’s poverty rate in half since 2004, from 48.5% to 21.7%. Perú ranks in the world’s top five producers of silver, zinc, tin, lead, copper, and molybdenum.

At the same time, the mining boom has left many indigenous Andean communities behind. Tax revenues generated by the mines have generally benefited Lima and not the regions where the revenues are earned. The workers filing out of the bus in Oyón primarily represent a skilled labor force from the coast, since modern-day mechanized mines offer limited employment opportunities for uneducated, unskilled local labor. Meanwhile, pollution, water usage, and land usurpation have driven indigenous communities to fight back against several large mining projects. In some cases, protests have laid waste to billions of dollars of foreign investment as projects have stalled or folded, most notably at the Mina Conga in Cajamarca and Tía Maria in Arequipa, two projects which combined to $6.2 billion of investment. In each of these cases, protests resulted in the deployment of national armed forces and a handful of deaths and injuries. Mina Conga was abandoned and Tía Maria is still stalled under governmental review, since 2015.

Approaching Oyón, I biked upstream to the headwaters of the Río Marañon, through a valley with a series of bright blue lakes, each more brilliant in the last. Despite the beautiful, clear water, I made sure to refill my bottles from streams cascading off the valley’s cliffsides, instead of the lakes. I knew from research that a mining operation sat at the top of the valley, so the lakes could potentially contain tailings, the toxic byproduct of mine activity, which my water purifier would not combat. Sure enough, I eventually arrived at a lake with a slight dark tint at its mouth. Above this lake, the growl of heavy machinery and intermittent explosions echoed off the walls of the basin.

Minera Raura, at the top of a 15,600’ pass, has pulled lead, silver, zinc and copper out of the surrounding peaks since the 1920s. As I biked along the access road through the mine, I observed toppled mountains and drained lakes that left stagnant, discolored puddles. The sight certainly disappointed me after the beauty of the lakes below. What had this summit looked like before they tore it apart? I wondered if tailings would continue to pollute the blue lakes downstream over the years, where only a few villagers and farmers lived. I wondered if these communities would have the political sway to contest the negative environmental externalities from an economically successful mining operation.

I found out that Minera Raura has a long history of local environmental controversy, but its relative remoteness has allowed it to slide under the radar of nationwide uproar that devastated the less remote, more expensive projects of Mina Conga and Tía Maria. But the provincial government still recently managed to burden Minera Raura with significant charges for discharging waste into the lakes in excess of regulatory standards, and resultantly displacing the population of a small town due to health concerns. The mine was forced to pay a fine of 7.7 million soles ($2.5 million) between 2006 and 2015. New management arrived in 2016 with promises to be better stewards of the community, while the outgoing directors avoided jail time by vehemently denying the government’s findings.

After leaving Oyón, I rode up a 16,100′ pass with yet another ugly mine at the top. This one, however, had no towns or settlements immediately below it. I couldn’t find any information about it online. With no threat of community activism, I wondered how strictly this mine had to adhere to environmental regulations. I wondered whose investments these were and where the tax revenues would be deployed. I wondered if the mine employed locals or limeños. I wondered if its pollution would eventually reach the drinking water of Oyón, or even Lima. All the wonders with so little answers began to frustrate me. But all I can do on a bicycle is wonder. Especially given the irony that, without the mining company, I wouldn’t even have these backcountry dirt roads to enjoy.

Bibliography

https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2016/02/06/from-conflict-to-co-operation

http://pagina3.pe/oefa-multo-con-s7-mllns-a-la-minera-raura-por-contaminacion-ambiental/

2 comments

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

I’m loving the blog posts! You’ve done a great job of making each one so much more interesting than a rote “First I went here. Then I went there.” They raise more questions than they answer: the sign of first-rate writing.

Andrew, thanks so much for the kind words! Means a lot coming from a travel and bike touring aficionado like you! I’ve also found that writing about specific topics, and trying to derive lessons, conclusions, or just questions from those topics, helps me personally both contexualize my experiences and learn more from them. For example, without the blog, I would have just thought – “huh, that’s an ugly mine,” and moved on. It’s been a rewarding way to travel! And I’m lad that it makes for a more interesting read, too.