No puedes controlar la lluvia, cápitulo dos

ColombiaThis is part two of a two part series. Events are factual but the descriptions may be subject to exaggeration, in the spirit of the great Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s style of magical realism.

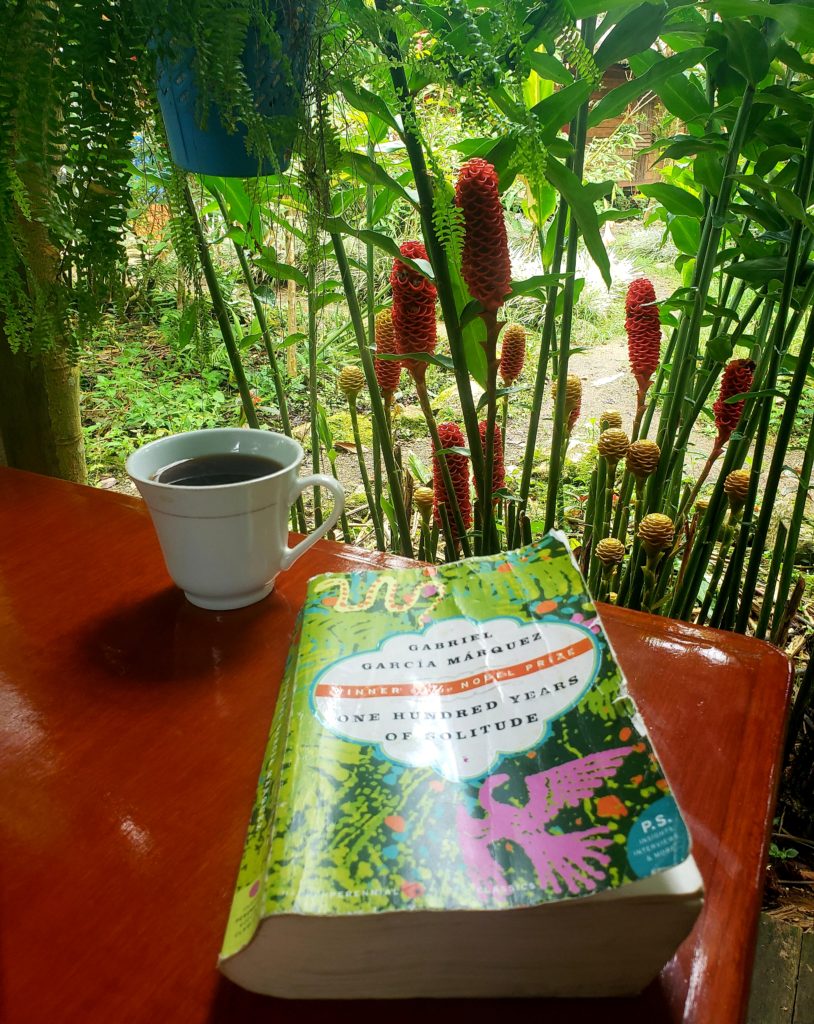

Rain fell in the rainforest of Mocoa through the night and into the next morning. The tin roof of the hostal transformed the rain into a deafening storm in my mind, as I spent a two-hour breakfast reading Cien Años de Soledad by Gabriel Garcia Marquez over countless cups of coffee, hoping that caffeine would restore my power to control the rain.

It was raining in the book as well – the rain lasted four-and-a-half years. Aureliano Segundo had been on an errand to his family’s house when the rain started (he lived with his mistress), and was too lazy to leave until it cleared up, so he waited patiently inside year after year while the deluge continued. What if it rained for four-and-a-half years here in Mocoa? I didn’t have the luxury of waiting that long; moreover, Aureliano Segundo’s sloth, adultery, and hedonism disgusted me, so I closed my book and ventured out into the rain.

I went on a hike to a local waterfall, named “Fin del Mundo,” fully armored in all my rain clothes and immediately became drenched on the inside from sweat in the heat of the jungle. So I removed my rain gear and carried it while the rain fell on my bare back. Arriving at the “end of the world” involved two waist-deep river crossings, which were then repeated on the way back. My useless nylon shoe covers were swept away in the current. Upon returning to the hostal, I was wetter than the river itself and when I took off my shoes I saw that I had taken a couple of souvenir waterfalls back with me.

But my sorcery had clearly returned. As soon as I entered the hostal, ready to nap and finish my book inside, dry like Aureliano Segundo, the rain ceased, the sun shined, and I saw a clear view of the canopy of the Amazon for the first time. The sun persisted throughout the next day as I made preparations for the next stage of my ride: a road called “El Trampolín de Muerte,” called such because many cars and buses had historically fallen off the cliffs that the road is carved into, bouncing to their deaths after being swept off by landslides or rivers or simply driving too fast around one of the many hairpin turns. Having spent much time on trampolines as a child, I thought I was prepared to avoid such a fate.

Early in the morning of my departure, the rain returned. I left in the dark before any of the shops opened. I took a bite of the danish I’d bought the night before and spit out a mouthful of ants, so I had oreos for breakast instead. Every muscle in my face was tense and retracted to avoid the biting rain, and I knew that only a cup of coffee would relax them, but coffee wouldn’t be available until I arrived at a tienda halfway up the mountain. I could see the tienda – it was directly above me, a vertical mile up the cliff. The road slashed mercilessly long switchbacks, through rivers and under waterfalls, around hairpin turns with caution tape for guardrails, over the rubble from massive landslides, past crucifixes memorializing victims of the trampolín — and all the while, the cup of coffee that would relax my contorted facial structure was the sole inspiration to push the pedals stroke by stroke ahead.

I wondered when the landslides occurred. They couldn’t have been recent, I thought. And in response to my inquiry, I heard a rumble behind me as debris peeled its way off the mountain and scattered into the stretch of road I had passed minutes earlier.

After ten hours of contouring the infinite mountainside, I emerged from the Trampolín onto a perfectly flat plateau, the Valle de Sibundoy. I could barely balance on the flat land after finally becoming comfortable teetering on the edges of cliffs all day. The people of Sibundoy wore thick wool ponchos and patterned hats, and the roads were quiet, the melody of the rain replacing the usual vallenata and bachata that typically blasts from billiards halls at the crossroads of Colombian pueblos. A woman bicycling in the opposite direction carried a bundle of crops hanging from her seatpost. At the sight of the similarly heavy load on my bike, I think she smiled, but not with her face, as that would be too friendly for this cold part of the world.

I arrived at a hotel with an immaculate white tile floor, and my filthy bike bled a trail through the hallways as a young man followed me with a mop. When I stopped, he continued mopping circles around me as if he never did anything else with his days but mop these white tiles. The host addressed me as “Don Brian Dennis” in old Spanish formality. I gave him my wet clothes to wash and dry, and he gave me the keys to my room and a bottle of shampoo that smelled like bubblegum. Then I collapsed into a deep sleep, deep enough that I forgot about the rain for a few hours.

But in the morning, it was still raining when the host returned my clothes. “Más o menos seca,” he said. The clothes were still soaking wet. He may not have known the difference, or maybe clothes never actually dried in this strange valley without sun, where they can’t control the rain.

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||