Siempre tengo hambre

PerúThe cecina in front of me looked like a smashed cow patty atop a bed of rice and plantain. I had adhered to my standard menu gamble that helps me learn more about the local cuisine: I ordered something I don’t know what is. I was a little nervous at the sight of what I’d done. But by this point, I had enjoyed enough meals in Perú to trust that it likely wouldn’t taste like cow dung.

Immediately after I’d crossed the border into Perú, my palate had been overwhelmed with flavor and spices. For my first meal, I had devoured a plate of chaufa and tallarines at a chifa restaurant. On paper, that means fried rice and lo mein at a Chinese restaurant. Combined, they become a dish called an “aeropuerto.” Logic has abandoned that translation. Supposedly, chifa is a fusion of Peruvian and Chinese cuisine, born in the early 20th century when thousands of Chinese laborers settled in Perú. I can’t put my finger on what exactly makes it different than the Chinese food I’ve had in America – but the Peruvians added some sort of spice that made me crave more and more chaufa, without my stomach combusting internally from the grease in fried rice I was used to from back home. Or maybe I had just been famished. Fortunately, seconds were available. “¡Otro, por favor!”

The next day came the lomo saltado, a simple enough dish — stir-fried beef with onions, peppers, rice, and french fries — that I had washed down with a jar of chicha morada, a refreshing and ubiquitous Peruvian beverage made from red corn. After dreaming all night about lomo saltado and chicha morada, I had returned to the same place for breakfast the next morning and ordered the exact same thing.

Later that day, at an open air patio off the highway in the middle of nowhere, I had stopped to eat lunch out of necessity. Between towns in Colombia and Ecuador, I rarely found meals better than a soup with strange animal parts floating in it, or a slice of unseasoned meat with undercooked rice. So I didn’t expect much here other than fuel to keep my legs churning toward the next town.

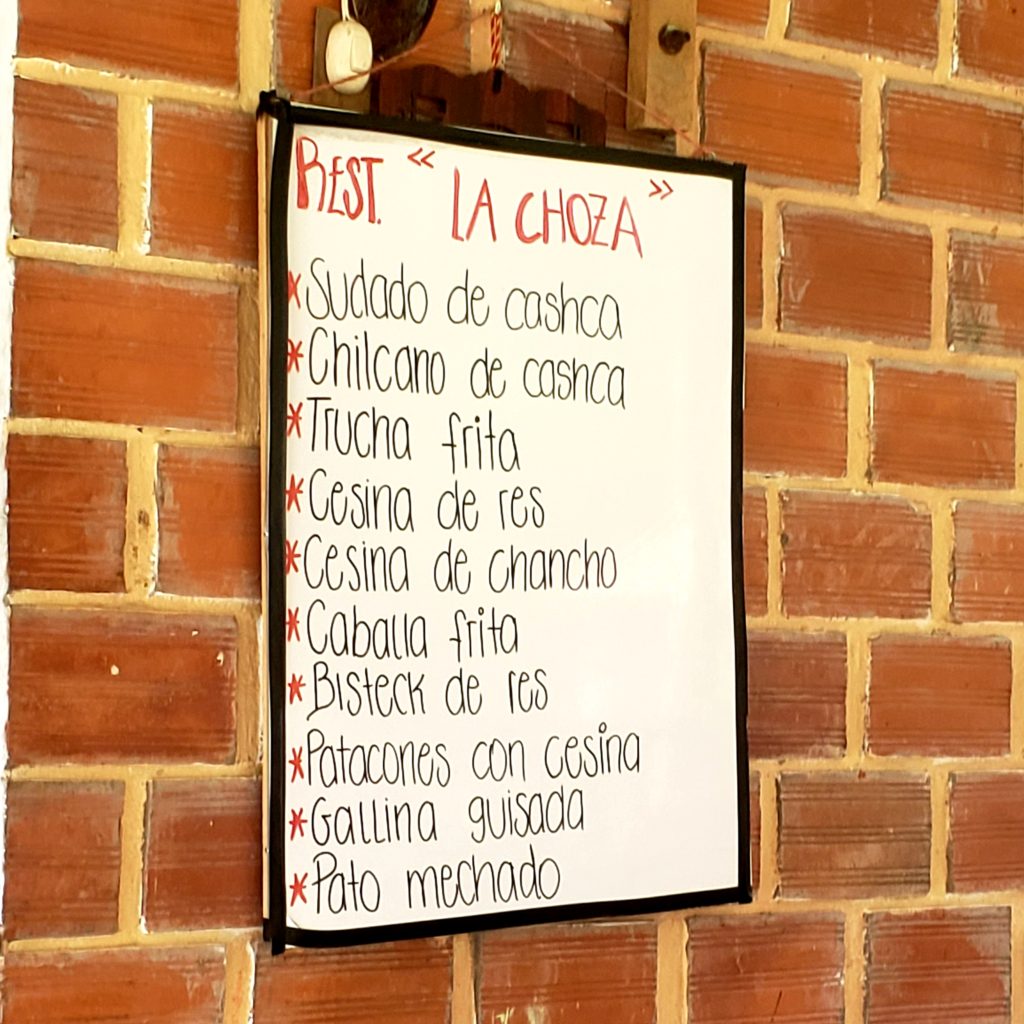

“¿Qué es una cashca?” I asked, picking out an unfamiliar word from the whiteboard on the wall, per my rules.

“Puedo mostrarte,” she said. She walked to her fridge and pulled out a tray full of catfish. “Muy rico.”

“Ok, bien.” I was sold by her enthusiasm.

“¿Chilcano o sudado?” she inquired. I didn’t know what either meant.

“Sudado,” I chose blindly. I learned when the dish came out that sudado meant stewed, with vegetables and spices. Vegetables and spices! They should export some of those to Ecuador, I thought.

The cascha was a winner, but poking at the smashed cow patty they called “cecina,” not knowing what to do with it, I wondered if I just lost the menu gamble. The pokes rendered a texture which was stiff and a bit crispy. It looked like it had been cooked seven times over.

The cecina found its way to my plate in the tiny pueblito of Cocachimba, home to one of the world’s tallest waterfalls. As the story goes, this pueblo’s indigenous people never thought to spread the word about their sacred natural wonder, oblivious to the fact that gringos love waterfall hikes and will pay mucho soles for a good selfie opportunity in front of falling water. Then, in 2002, a traveling European caught a glimpse of the waterfall. Soon enough, a trail was paved, hotels were built, restaurants were opened, and gringos started flocking to Cocachimba to see la Catarata de Gocta.

From my experience in far flung pop-up tourist destinations like this one, cooked food is usually an over-priced commodity, not a profession. I wouldn’t have been surprised if my cecina had actually been cooked seven times, as if the restaurant heated it over and over after guests politely declined it.

But when I finally hacked off a bite-sized piece and tasted it, my mouth was overcome with wonder for the smoky, salty, juicy slice of dried meat, perfectly balanced by rice and plantains.

“Que rico,” I told the cook, a young guy who doubled as waiter and host. He told me it was a specialty of the Amazonas province and that he had just learned to cook it, but that he had studied the theory of smoked meats with a chef from Texas at a university in Chiclayo, on the Peruvian coast.

A chef with a culinary degree in this tiny village? How did that happen?

He loves food, he told me, but he also loves traveling. He has lived all over Perú, and had spent the last year making his way through Brazil, Argentina, and Chile, working for a few weeks at a time in kitchens, learning the local cuisines. He had taken cooking classes in France and was trying to line up a stint at a Peruvian restaurant in New York City. Just as I am using my bicycle as a way to experience new parts of the world, he is using kitchens.

I’ve never been much of a foodie, but an insatiable appetite brought on by constant physical exertion has led me to structure many days around optimizing food opportunities. I have also enjoyed seeing traditional culinary practices gradually morph from region to region. However, in Colombia and Ecuador, despite the charms of local delicacies, I often looked forward to finding the familiar flavor of pizza or Thai noodles in larger cities. But after just a few days in Perú, I no longer had any pizza cravings.

“¿Vas a Lima?” he asked me.

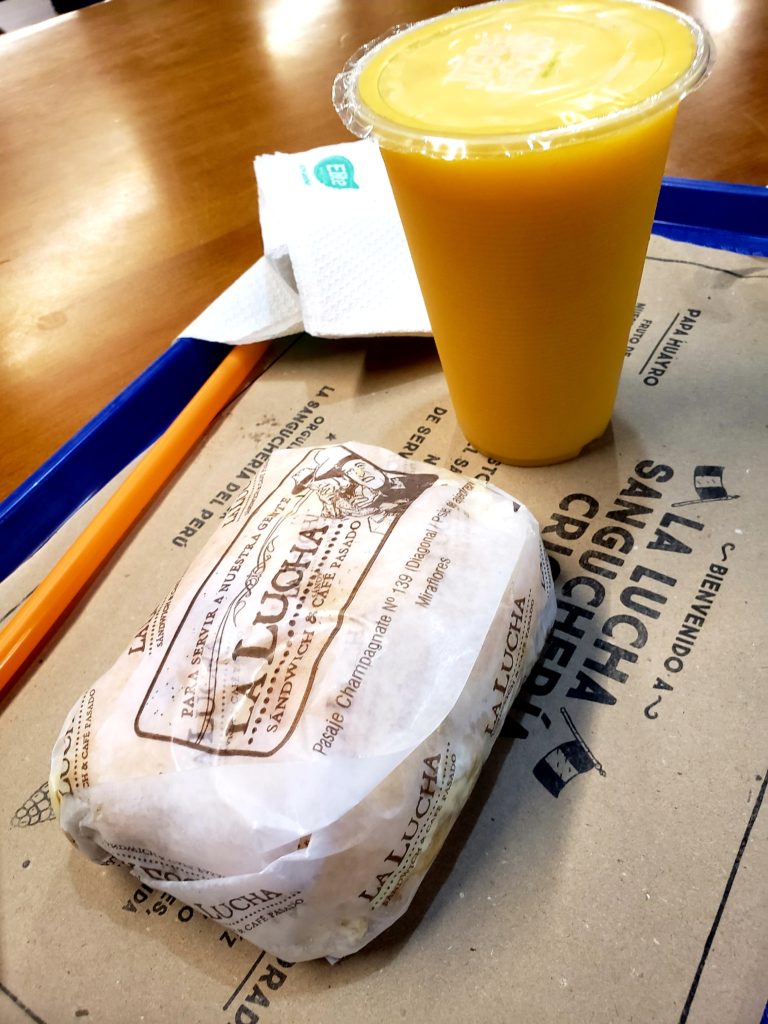

“Si.” I would fly to Lima next week to meet Liz for a little vacation from the bicycle.

“¡Disfruta el ceviche!”

I knew I would.

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |