Un cuento de dos campesinos

Colombia“Tinto, por favor.”

Surrounded by mountainsides blanketed in coffee beans in Quinchía, the heart of the zona cafetera, I thought it might be safe to order a coffee black.

“Buen provecho,” he said as I took a sip. He must have seen me grimace since he pointed at the condiments in the middle of the table. “Azucar, y panela.” I plopped a big scoop of panela, which is basically unrefined sugarcane and a delicacy here, into my tinto to ease the bitterness.

Quinchía is no exception – it’s actually tough to find decent coffee in coffee country. Colombia is the world’s third largest coffee exporter and even better known for its quality than quantity. But the key word is: export. They sell the good beans to other countries. The beans that were ground into my tinto in Quinchía? The ones that didn’t make the cut. Colombians prefer their chocolate caliente anyway.

I will drink tinto as bitter as need be, though, because I can’t wake up without it. But I wanted to see where the good stuff comes from. So I visited two separate fincas, of John in Jericó and Alfredo in Filandia, to learn a bit more from the campesinos who grow this miracle plant that provides for both my functionality and the region’s economy.

John picked up Angelo, my airbnb host in Jericó, and me in his old Jeep. The two of them, old buddies, cracked jokes and talked smack about other townfolk, alternately criticizing and complimenting neighbor coffee crops that we passed. We pulled into John’s finca – a sleek A-frame lodge that he marketed as a “Coffee Hostel,” where tourists could embrace the campesino lifestyle in luxury. His housemaid served us a chicken dish with a “salsa de cafe” that might as well have been from a Bogotano restaurant. After lunch, John used a vacuum brewer and a French press for separate taste tests of his product.

~

Alfredo, at the other finca in Filandia, welcomed me into the tiny kitchen of his brick house where his wife was cooking. The skinny building, barely more than a shack, took up all of the ten meters between the dirt road and the ravine where the coffee grew. I sat down at the table next to his two daughters who were working on a coloring book. The five of us ate a plain but filling meal of beans, chicken and rice. After lunch, Alfredo boiled some water on the rusty stove and poured it over a few scoops of coffee from a nondescript jar on the cabinet.

~

John, back in Jericó, with his neatly trimmed mustache and traditional yet chic panama hat, tossed us a couple baskets and sombreros and set us to work picking the red fruits that were ready to harvest. Angelo diligently picked while I lazily took pictures and marveled at the variety of fruit trees – bananas, platanos, mangos, lulos, guavas – that provided the coffee plants with shade they need to grow best. John asked if I thought that Americans would enjoy volunteering at his finca to learn about coffee. Free lodging for them, free labor for him. I looked down at my mostly empty basket and said it might be a bit optimistic.

~

Alfredo, on the other hand, barely five feet tall, wore a blue polo that read “Fuerzas Armadas” with a Colombian flag. I tried to remember what that was – the Caldas soccer team? Only later would it hit me – the first two words of “FARC,” the notorious left wing guerrillas that drew a surprising amount of political support in the countryside. He also wore big rubber galoshes and a machete around his waist and handed me a second pair of galoshes and some rain pants, telling me we’d go on a hike before talking coffee. “Está bien,” I said; I had my own hiking shoes. He insisted, which I appreciated, because the hike was actually a long-distance wade through a creek to a few small waterfalls. He macheted some plants out of the way and stopped to admire others, showing me flowers which you can drink water from like a cup, vines you can use as rope, and ferns which are used to wrap tamales.

~

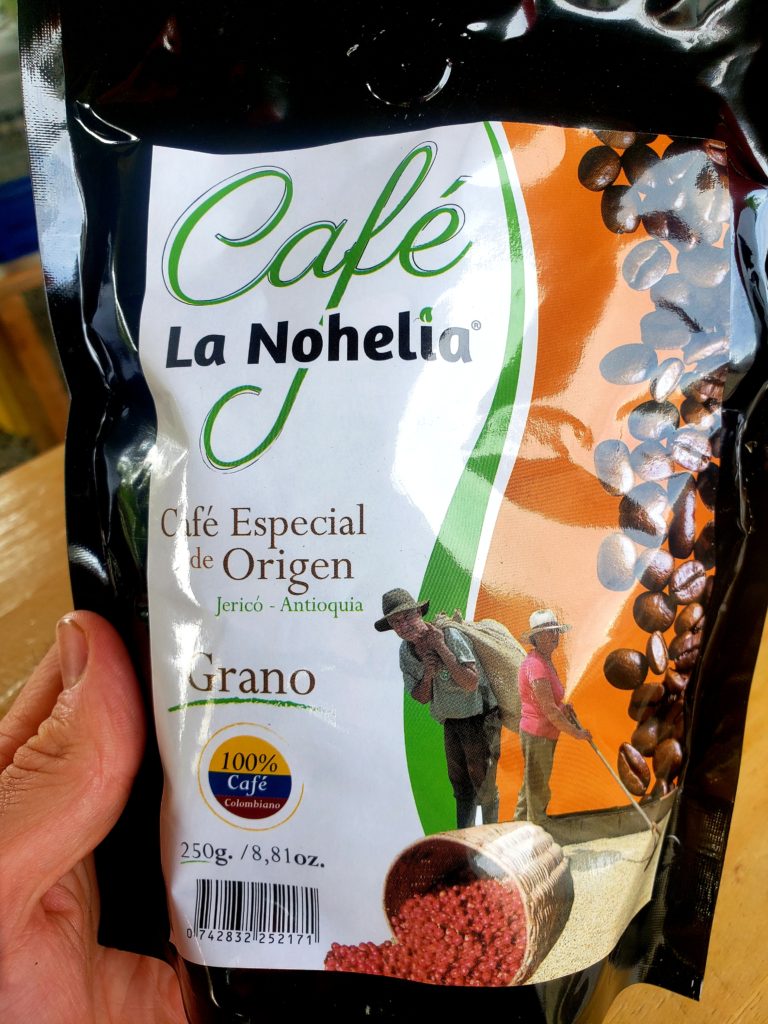

John, when he’d had enough of my lazy work in Jericó, took our beans to his workshop where he used automated machines and Rube Goldberg-like processes to peel the fruit’s skin, dry the moist beans, sort them by quality and size, peel the shell of the bean, then finally roast them in an industrial oven, and grind them into plastic pouches branded Café Nohelia. He barely touched the beans throughout the process.

~

Alfredo didn’t have any of the fancy tools. He used a fruit peeler with a manual crank, the same that John kept in his living room to show off as an antique. Alfredo then carefully spread the beans on a towel on his porch to dry. He sorted the dry beans by hand, individually removing each bad bean, then peeled the shell of the beans by rubbing them between his hands. He roasted them in a pot on his stove and then ground them in the kitchen while his daughters complained about the noise, before packaging the coffee into paper bags that he sealed shut with a steaming iron.

“Campesino” literally translates to “peasant” in Spain Spanish, but the Colombians that pick coffee beans wear the nomenclature proudly. The coffee growing industry in Colombia industry is made up of many individual, family-owned farms, like John and Alfredo’s, in contrast to large corporate plantations found in other coffee-producing nations like Brazil. However, coffee is a commodity with exports measured in the millions of tons, and it is tough for the campesinos to earn a living without the scale of global competitors, particularly with recent markets impacts like Brazil’s currency devaluations and supply spikes of lower quality Vietnamese beans. Because of the low prices, neither John nor Alfredo sell their beans to export. John sells mostly to boutique cafes in Medellín and online. Alfredo sells his coffee in his house-front tienda, primarily to his neighbors. But they also grow and raise all the food they need to live off the land – and are happy in their corner of the world.

As I biked out of Filandia, Alfredo was out front of his house. I waved and he beckoned, “Cafecito?” I’d already had two cups of his coffee at the hostal, but I couldn’t turn it down. Who knows when I’d find another cup of tinto that didn’t require a big lump of panela?

2 comments

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Mar | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Great blog so far. Especially loved this post with the juxtaposition. And unbelievable Strava elevation profiles.

You’re really making me want to get back out there again.

Thanks man! Come join!!